December 10, 2011–March 4, 2012

THE POWER PLANT CONTEMPORARY ART GALLERY

The winter season at the Power Plant opened with “two major exhibitions that delve into a wellspring of cultural history and the archive of the social.”

Stan Douglas’s photographs fill the two large halls on the right side of the gallery. His Entertainment: Selections from Midcentury Studio continues the artist’s practice of re-examining the past by recreating site-specific events. His staged photographs look like journalists’ shots of baseball games and other sport events from the 1950’s. In reality, the artist used actors and reconstructed the events to create “fake documentaries” in his studio in 2010. The sixteen black-and-white “portraits” of Malabar people were also staged using actors posing as patrons of an imaginary bar: elegant ladies wearing long gloves, dancers with pretty décolletages and waiters ready to serve. The large, noir-style images radiate a kind of dark charm from the postwar years.

Stan Douglas, Malabar People: Waitress II, 1951, 2010. Digital silver print mounted on Dibond aluminum. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York.

Stan Douglas, Malabar People: Waitress II, 1951, 2010. Digital silver print mounted on Dibond aluminum. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York.

On the left side of the gallery there are more intimate places, mainly projection rooms, leading into the other exhibition, Coming After. Currently, there is a renewed interest in the 1980’s and the birth of “queer” culture. The recently closed show, Haute Culture: General Idea, at the AGO focused on how three gay artists changed the art world and made their works recognized and collected internationally. Coming After is the art of the next generation, those born after 1970. As artist Sharon Hayes notes, “It wasn’t my friends who were dying [from AIDS]. It was people I was just beginning to model myself after, people I longed to become.” The works in Coming After offer a different, new queer sensibility as the artists all feel that they arrived too late, missing the heroism of the fight for human rights, and that, therefore, all that’s left for them is nostalgia. Susanne M. Winterling’s room initially appears empty, but as you move your shadow reveals words from funeral speeches.

Adam Garnet Jones, Secret Weapons, 2008. Digital video, 5:30 min. Commissioned by Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre (CFMDC) ReGeneration. Courtesy the artist.

Adam Garnet Jones, Secret Weapons, 2008. Digital video, 5:30 min. Commissioned by Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre (CFMDC) ReGeneration. Courtesy the artist.

Adam Garnet Jones’s video, Secret Weapons (2008), simultaneously shows images of a guy being beaten up, falling and standing up again; an insignia being tattooed onto someone; and a man talking. The man speaks about the importance of a unified group whose members must support each other—when someone falls the next person will always replace him. This video is very dramatic and reminds me that even if the days of heroic fights for gay rights may be over here, they are still going on in other places.

Dean Sameshima, Gauntlet II (LALC), 2003. C-Print. Courtesy the artist and Peres Projects, Berlin.

Dean Sameshima, Gauntlet II (LALC), 2003. C-Print. Courtesy the artist and Peres Projects, Berlin.

Seeing a series called Gauntlet II reminds me of when, in the summer of 2011, the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art saluted Cameron House with an exhibition called This is Paradise. Cameron House was not only a bar but a communal meeting place, a theatre and a gallery where gay culture was welcomed in the 1980’s. Dean Sameshima’s photographic series entitled Gauntlet II (2003) shows an empty bar that has seen better days and happier times. The artist creates a cold, sad atmosphere, but at the same time the warm light of the lamps give a little hope that someone might suddenly come in.

In Christian Holstad’s installation, The Road to Hell is Paved (2009), discarded shopping carts, ramps and wrapping materials stand as archaeological reminders of consumer culture, wished dead by the artist.

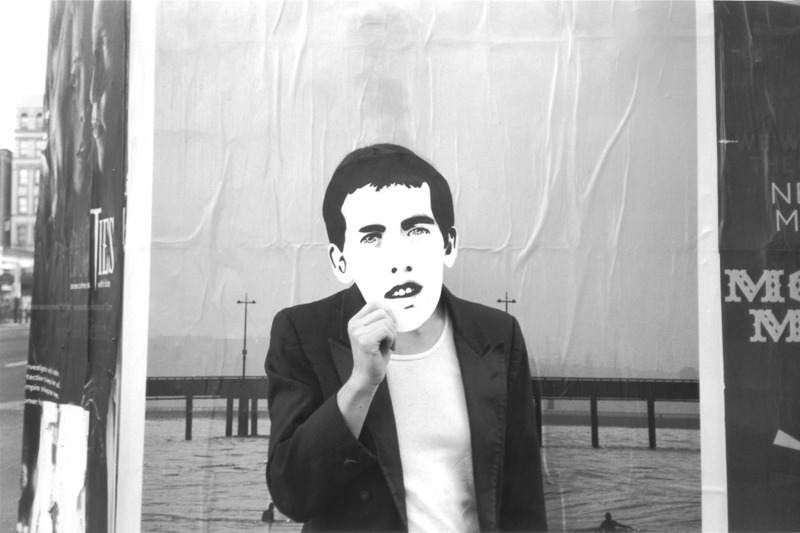

Emily Roysdon, untitled (David Wojnarowicz project), 2001–07. Twelve black-and-white photographs, two embroidered. Courtesy the artist

Emily Roysdon, untitled (David Wojnarowicz project), 2001–07. Twelve black-and-white photographs, two embroidered. Courtesy the artist

On the second floor I found Emily Roysdon’s untitled collages (David Wojnarowicz project, 2001-07) very disturbing. In these pieces, Roysdon honours her teacher, Wojnarowicz, who taught her the meaning of queer culture through his art and personal example, by identifying with him through role playing. A female figure wears a mask of a young man in different situations—in bed, in a crowd, in a group of her friends—all with a sad expression, showing the enormous pain of being different.

Then there are Danny Jauregui’s three monumental paintings depicting the bath houses, one of the most important scenes of early gay culture. I remember artist Alex Liros talking about the early 1980’s bath houses in Toronto, the active life in those meeting places, the danger of police raids, and the beatings that followed. Jauregui’s paintings show the now closed down and abandoned bath houses, Hyperion Health and Basic Plumbing (2010), as mementoes of an era that has disappeared.

Glen Fogel’s movement-activated neon installation, Glen from Colorado (2009), ignored me and didn’t start at first but then began to flicker and talk about identity. Unlike the other more nostalgic pieces in this show, Fogel’s work brought us back to the present.

Emese Krunák-Hajagos