Edward Burtynsky

Water

Nicholas Metivier Gallery

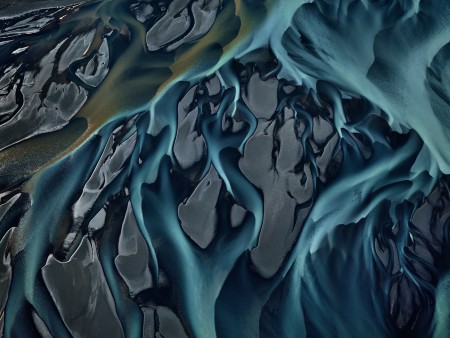

Thjorsá River #1, Iceland, 2012, chromogenic print. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

Thjorsá River #1, Iceland, 2012, chromogenic print. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

After spending over ten years poring over the theme of oil, Edward Burtnsky has turned his camera to a resource no less politically fraught but much more ubiquitous. The Canadian photographer dived into this ostensibly familiar subject back in 2008, a project that carried him to across the globe from Iceland to China, and from India to Spain. His work navigates meditatively through the ubiquity and complexity of water, revealing the myriad physical and emotional ways in which humans relate to it. Photographs from this project are currently showing at a series of galleries internationally in tandem with his latest documentary, Watermark. In Toronto, a selection of Burtnsky’s work is hosted by Nicholas Metivier Gallery, showing across two locations until October 12, 2013.

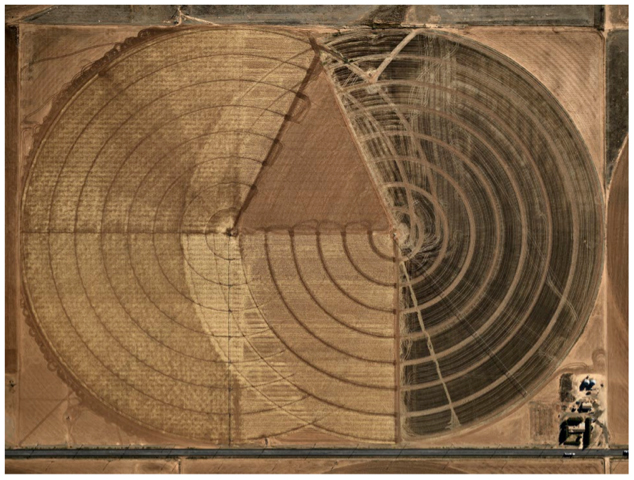

Pivot Irrigation #1, High Plains, Texas Panhandle, USA, 2011, chromogenic print. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

Pivot Irrigation #1, High Plains, Texas Panhandle, USA, 2011, chromogenic print. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

Water is a word that conjures up very mixed feelings. It is a primordial source, an invaluable resource, a holy purifier, a picturesque scene, a victim to human callousness, and an unruly, destructive force. The photographs in Burtynsky’s water project, beyond just covering vast geographical grounds, also manage to capture a wide span of these emotional and cultural associations. His photos of pivot irrigation farms in the Texas Panhandle explore the role of water in enabling human sustenance, and the technologies that mediate our resource use. These images, like many other works in the water series, adopt a high aerial perspective that renders the irrigation system into curious and abstract compositions of concentric circles. Further twisting the practical into the strange, the crisp detail signature to Burtynsky’s photographic work imbues the circular plots with sensuous texture, evoking imagery of a spinning vinyl or the stump of a millennia-old tree.

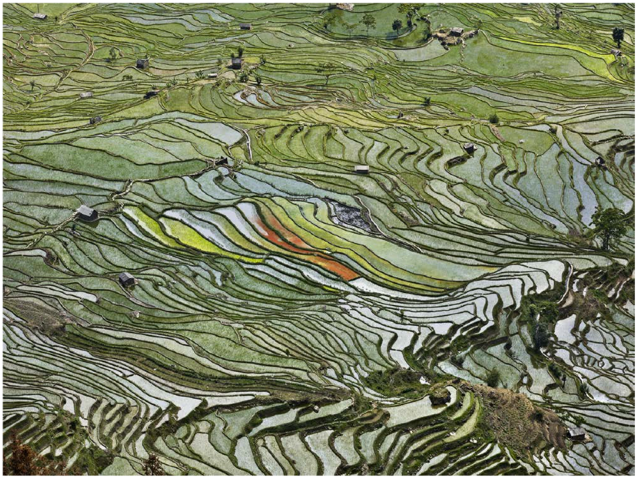

Rice Terraces #2, Western Yunnan Province, China, 2012, chromogenic print. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

Rice Terraces #2, Western Yunnan Province, China, 2012, chromogenic print. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

In northern British Columbia, the photographer encounters the sublime beauty of the Stikine River, which flows in a sinuous languor in between towers of rock that thrust up on either side. The rugged view recalls the Canadian landscape tradition inaugurated by the Group of Seven, and the long-existing ties between our national identity, the land, and its bounty. Though oil seems to be the resource de jour taking a front seat in our national consciousness, Canada and the politics of water go further back. Our nation contains one fifth of the entire world’s fresh water, and this valuable endowment has spurred desires and debates over the privatization, commodification, and export of water. Within the cultural realm, Joyce Wieland was already tackling this theme back in 1970 with her work Water Quilt. This quilted work incorporated sixty-four excerpts from James Laxer’s The Energy Poker Game, a foreboding political book on an alleged American plot to take over Canada’s water resources.

Greenhouses, Almira Peninsula, Spain, 2010, chromogenic print. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

Greenhouses, Almira Peninsula, Spain, 2010, chromogenic print. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

In exploring myriad human attachments to water, it may strike as a curious observation that the photographs in this show are largely devoid of actual human presence. Burtynsky explains, however, that he is less interested in the individual’s relation to water than in our collective impact on water systems through history to now. In many of the photos, man-made constructions stand as placeholders for the human will to progress. A photograph of marine aquafarming in Luoyan Bay in Fujian Province, China is particularly unsettling. Rectangular grids of aquafarms nestle one next to another in systematic indifference; their regularity is momentarily disturbed by a rock formation rising through the water, but the plots weave around and extend unfazed and relentlessly into the horizon. The photograph is an affecting reflection of capitalist culture and its paradigm of overconsumption, resource depletion, and faith in technology to fix it all. The image, perhaps inconveniently, throws into question the growth imperative within contemporary political and economic mindset, and the simplistic straight line it draws between growth and progress.

Colorado River Delta #3, Near San Felipe, Baja, Mexico, 2012, chromogenic print. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

Colorado River Delta #3, Near San Felipe, Baja, Mexico, 2012, chromogenic print. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

In an oft-quoted lyric, Keats asserted that beauty is truth, and truth beauty. If so, Burtynsky’s beautiful photographic images bring up some ugly truths. In many of his works, a tension hangs between the pleasing formal elements and the unpleasant topical matter. In a shot of the Colorado River Delta, a green river gleams in stillness, branching like a capillary through a desert of white, crusty land. The visual impact is arresting and astonishing. Yet the image is also a sad footprint of what’s beyond the frame, of the multiple upstream dams constructed in the last century that have transformed the delta landscape into a shrunken ghost of its once expansive wetlands. The impact of undeclared human activities thus echoes through the picture, cutting across the quiet beauty of the barren scape.

Kumbh Mela #2, Allahabad, India, 2013, chromogenic print. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

Kumbh Mela #2, Allahabad, India, 2013, chromogenic print. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

On this tension between the aesthetic and the topical, Burtynsky says his images are “beauty on certain terms.” On the one hand, his approach to photography aims to embrace beauty again, despite its falling status within Western art in the last century. On the other, he hopes the viewer engages beyond the visual surface to discover something more than just retinal titillation. Though Burtynsky’s work is inflected with environmental undertones, his visual language is never didactic or polemical. His images are stoic rather than confrontational, and open-ended rather than explicit. Avoiding the trap of propagandistic art, which tries to sell a pre-packaged idea, Burtynsky intentionally employs an open-ended delivery to leave space for the viewer to feel, explore, and discover on their own. For me, the water photographs are political art in so far as they heighten my sense of the political, social, and ethical dimensions of my being. But this is as far as Burtynsky is willing to nudge me, as he said at the opening reception, and after that, it is up to myself as the viewer to decide where I want to go.

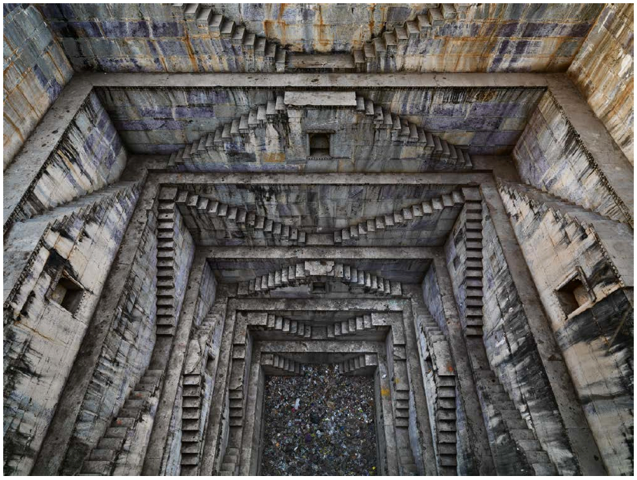

Step-Well #4, Sagar Kund Baori, Bundi, Rajasthan, India, 2010, chromogenic print. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

Step-Well #4, Sagar Kund Baori, Bundi, Rajasthan, India, 2010, chromogenic print. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

Amy Luo

*The exhibition is on display till October 12, 2013, Nicholas Metivier Gallery at 451 King Street West and and a temporary space at 80 Spadina Avenue, suite 404.