Art has many faces and artists find their voices through explorations in prevailing aesthetic traditions, art historical culture and personal circumstances. In some cases the resulting art reflects where they came from and their early life experiences. Marcelo Suaznabar is an artist who began his life in the Altiplano region of Southern Bolivia. This area is marked by large, inhospitable tracts of rugged scrub and bush, much like a desert. His father had a farm there so Marcelo has an instinctive relationship with animals and landscape.

Marcelo Suaznabar, The observer (El observador), 2014, oil on canvas, 60 x 4o inches. Courtesy of the artist and Articsok Gallery.

Marcelo Suaznabar, The observer (El observador), 2014, oil on canvas, 60 x 4o inches. Courtesy of the artist and Articsok Gallery.

Latin America has a complicated relationship with Christianity. The Spanish invaders who exported it, used it as a tool to subjugate and control the indigenous peoples. In the Colonial era, commerce, Christianity and civilization were philanthropic goals but the reality for the recipients was a form of slavery and servitude. Despite the professed ‘good intentions’, conquering nations also brought greed and lack of respect with them. It was logically expedient for indigenous folk to take on the mantle of Christianity to survive, and in a subtle way, they began to colonize it with their own belief systems. Thus the Christianity in Latin America is an amalgam of prevailing beliefs. It is marked by a sense of magic and mysticism that adds a richness which is not echoed in the dour, homicidal mentality of the Spanish Inquisition.

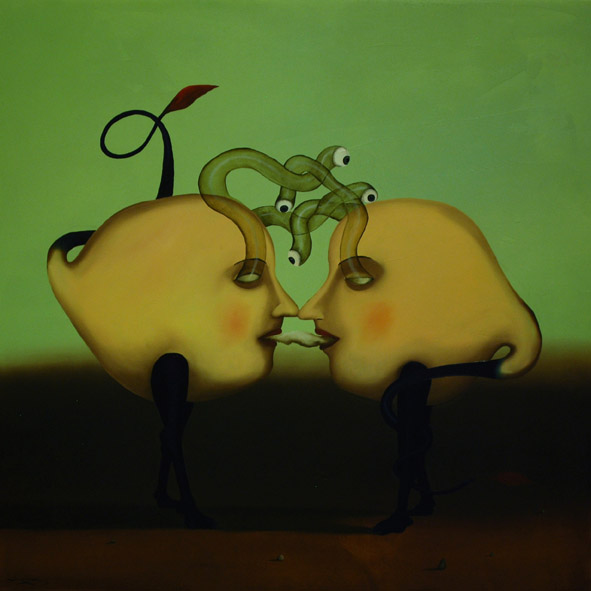

Marcelo Suaznabar, Political conversation (Conversacion politica), 2013, oil on board, 28 x28 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Articsok Gallery.

Marcelo Suaznabar, Political conversation (Conversacion politica), 2013, oil on board, 28 x28 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Articsok Gallery.

Suaznabar is also painting in the 21st century, which brings its own urgencies. Overpopulation and the decimation of the environment, the media-enraptured global audience who fawn over irrelevant celebrities while consuming unnecessary goods in ever-increasing quantities, ignoring the fact that global warming becomes ever more obvious and entire nations are sinking into extreme poverty. As a matter of conscience, Suaznabar is compelled to speak out through his paintings and try to alert or awaken viewers. Thus, he is a didactic painter in the tradition of Hieronymus Bosch. This is quite rare in contemporary art, where most artists are content to produce work that is in line with prevailing aesthetic trends.

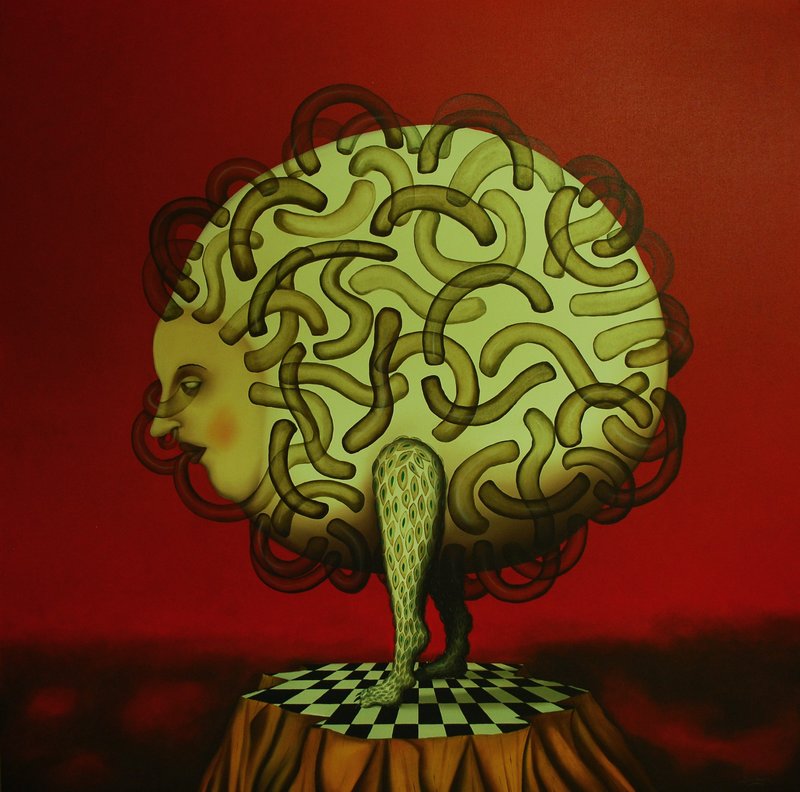

Marcelo Suaznabar, Still fragile (Naturaleza fragil), 2014, oil on canvas, 48 x 36 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Articsok Gallery.

Marcelo Suaznabar, Still fragile (Naturaleza fragil), 2014, oil on canvas, 48 x 36 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Articsok Gallery.

In fact, Suaznabar is engrossed in his life’s work and returns to the same themes quite obsessively; notably the Apocalypse. As one might expect, these paintings have a complex relationship with Christianity. Suaznabar recognizes the arrogance of the conqueror in the Christian message but also finds solace in the injunction that humanity is responsible for the planet’s wellbeing. In pagan mythology, Mother Earth, or Gaia, is a nurturing organism wherein all life forms are inter-dependent and none are pre-eminent. Christian mythology posits another world which chosen penitents reap a Heavenly reward after leading a ‘good’ (biblically prescribed) life on this earth. Entranced by the spiritual mystery of what could lie beyond, Suaznabar amalgamates the Christian perspective with an environmentally pagan view. As a visual messenger, he is obliged to use a metaphorical language that his viewers are familiar with, which in this case is the teleological interpretation of existence.

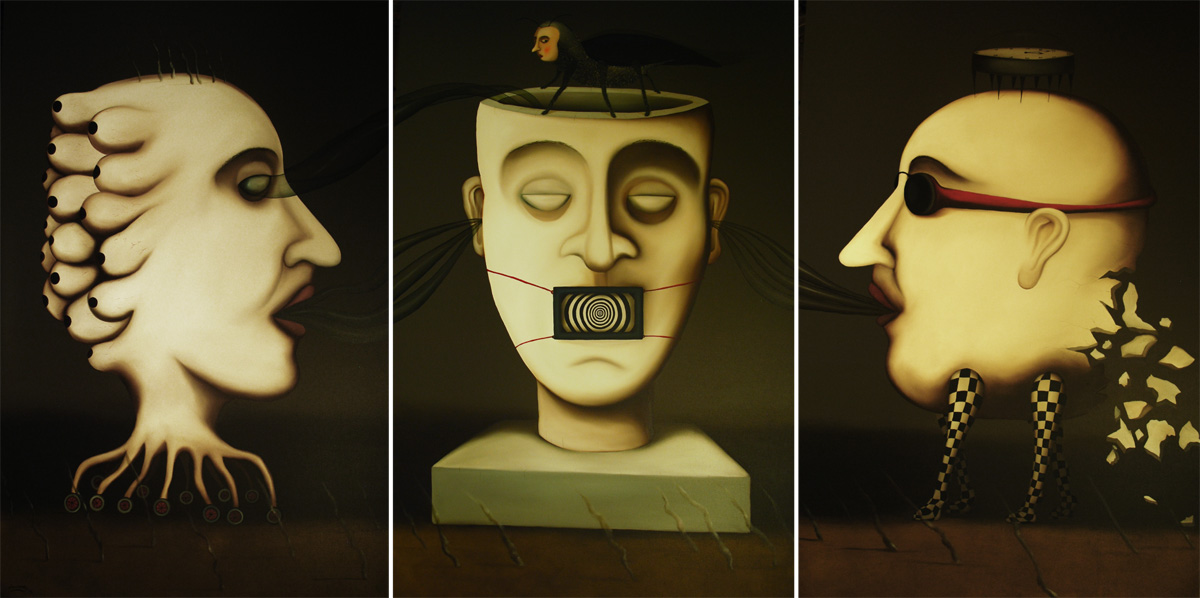

Marcelo Suaznabar, Wordless (Sin palabras), 2014, oil on canvas, 48 x 48 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Articsok Gallery.

Marcelo Suaznabar, Wordless (Sin palabras), 2014, oil on canvas, 48 x 48 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Articsok Gallery.

Thus, clocks are a persistent theme in his work and often replace faces. Salvador Dali, who was one of the most influential Surrealists, also used clocks. Dali’s brand of Surrealism was a hysterical, hyperactive realism that went through and beyond appearances to reach a truer reality; the Surreal. Thus form was just a membrane and ‘true’ reality was more like a dream where the usual laws of perception no longer applied. Suaznabar’s paintings have a Dali-esque flavour, in that form is always subverted leaving elements like roots or rivulets of blood sprouting from the ears of granite faces. Monolithic female forms stand like stone sculptures while small human figures deport themselves decadently. Hybrid animals and strange flying mermaids mingle with the human hordes. Sometimes their intention is malign and they consume their human prey but at other instances they tempt humans into folly.

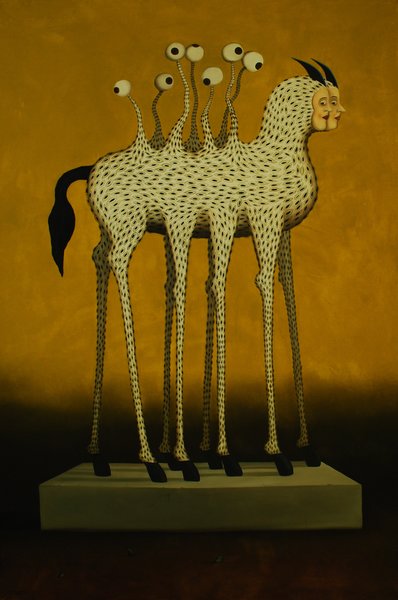

Marcelo Suaznabar, Out of sing, out of mind (Ojos que no ven, corazón que no siente), 2014, oil on canvas, 76 x 46 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Articsok Gallery.

Marcelo Suaznabar, Out of sing, out of mind (Ojos que no ven, corazón que no siente), 2014, oil on canvas, 76 x 46 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Articsok Gallery.

Suaznabar’s painting style is naive realist and as a consequence he can introduce humour too. Some of the animals are quite comical in their malign intention or languorous lounge, like the lobster-television that lies in wait for its prey, the woman (Contranatura). He delights in transforming and making unusual allusions. Thus a tree stands uprooted on a table. Furniture is used as a prop to present absurd ideas, like a four poster bed so high only a giraffe could reach it. Often he layers his canvases so there is a sense of the other world. He uses chiaroscuro to darken areas creating a nocturnal setting but with adjacent areas lit from another source, indicating a realm beyond.

Veneration for certain art historical characters like Frida Kahlo and Pablo Picasso is expressed in his Archangel series. Fragments of their work are woven into the structures, dominated by the ornate religious garments adorning the archangels. These works present an idealized pantheon of heroes who are respected for their contribution to art and humanity.

His Altiplano landscape series affirms the magical qualities that are transmitted through even seemingly desolate places. Fishlike creatures metaphorical of the strange and incomprehensible are immobilized on stands placed in the desert, evoking a psychological tension. Bright, swirling, otherworldly colours rip through the forms, contrasting an intense red with a celestial ultramarine blue or a green that is almost alien. Darkness suffuses throughout and the viewer peers anxiously into these crepuscular desert landscapes. Sometimes they are populated by figures from a circus like jugglers or harlequins riding elongated monocycles, sometimes by strange, multi legged beasts that slouch towards Bethlehem.

Marcelo Suaznabar, There is always something more (Siempre hay algo mas), 2014, oil on canvas, 72 x 144 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Articsok Gallery.

Marcelo Suaznabar, There is always something more (Siempre hay algo mas), 2014, oil on canvas, 72 x 144 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Articsok Gallery.

Suaznabar makes use of the Renaissance convention; the banner, through which he presents poetic text like “labyrinth of the passions”, indicating the meaning of the work. Language is transformed into a physical substance and pours out of mouths like ribbons. Certain symbols recur as in the egg, symbolizing the fragility of life or the cube which represents the constructed or manmade. Chequerboard of black and white squares take the place of landscape in many works, indicating human colonization of nature. The mechanical nature of human invention invades the natural order of things. The bar code becomes a ubiquitous presence, like a strip of duct tape over the mouth preventing a prisoner from speaking.

Ultimately, Suaznabar communicates at a vital level, since humanity seems to be on the brink of calamity. One can salute the intention of the artist to maintain a moral integrity and to present art with a social message. That he also creates mysterious and intriguing work is an added blessing.

Ashley Johnson

*Exhibition information: Marcelo Suaznabar: Beyond Appearance, June 19 – July 26, 2014, Articsok Gallery, 1697 St. Clair Avenue West, Toronto. Gallery hours: Wed – Sat 12 – 6 p.m.