Art Spiegelman at the press preview on December 17, 2014. Photo: Joséphine Mwanvua

Art Spiegelman at the press preview on December 17, 2014. Photo: Joséphine Mwanvua

We arrived an hour early at the AGO for the Art Spiegelman press preview on December 17th. I looked forward to this exciting experience and honor, because he is a legend in the world of comics. We had the opportunity to see the exhibition before the talk began. It is an extensive exhibition, in a large space, and with so many things to look at. I took my time to savour it methodically—by taking in the contents of a few comic strips and cover art at a time, and then moving on to find their sketches, so I could appreciate the time and dedication the artist put into them. While exploring, I came across certain pieces that made me laugh, and occasionally heard others laugh beside me as well. Art Spiegelman’s comix are humorous, strange – as a lot of underground comix are – but it also can become serious when he deals with sexual or political content.

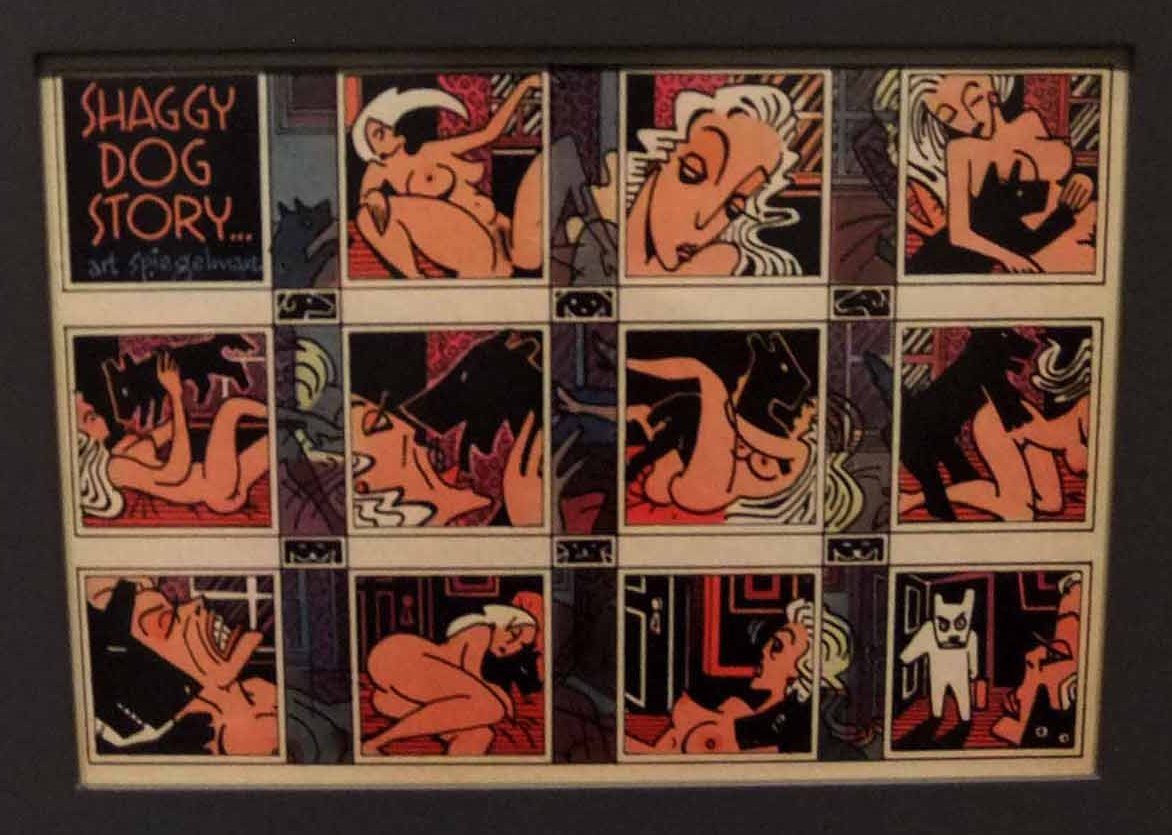

Art Spiegelman, “Shaggy Dog Story…”, Playboy magazine, Artist’s proof, 1979. Photo: Joséphine Mwanvua

Art Spiegelman, “Shaggy Dog Story…”, Playboy magazine, Artist’s proof, 1979. Photo: Joséphine Mwanvua

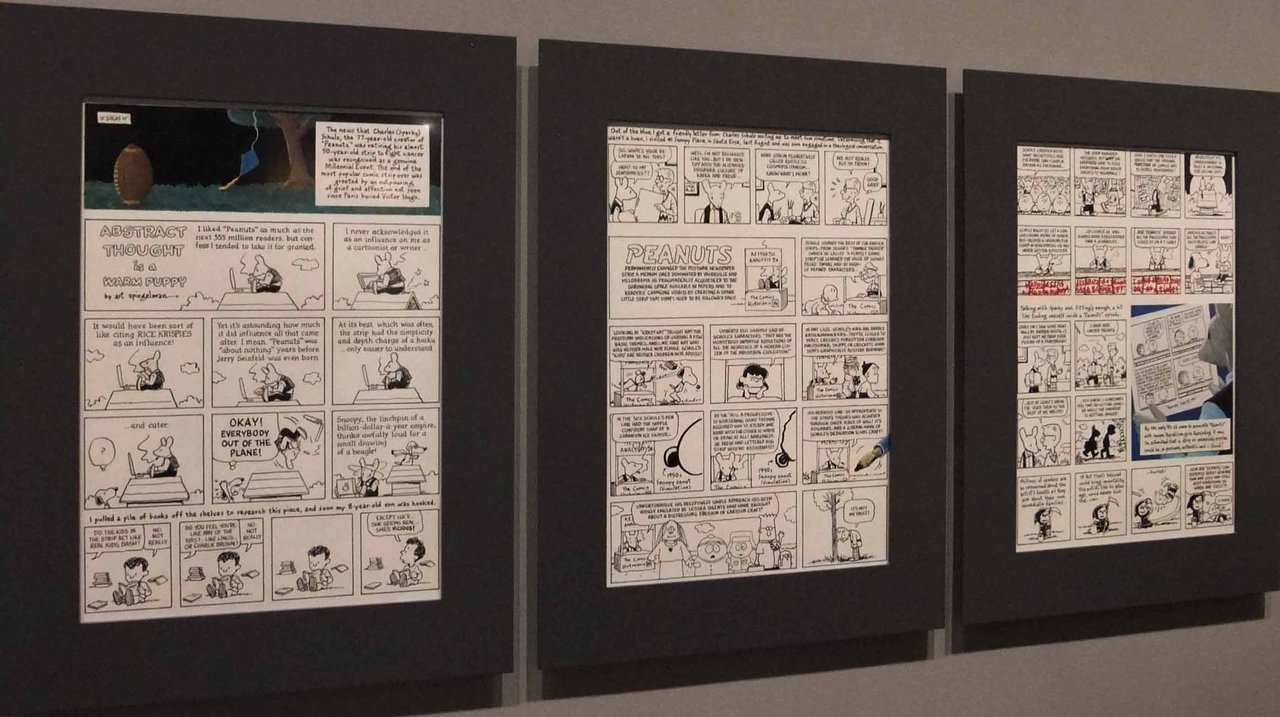

There is a difference between “comics” and “comix”: the word “comics” is used when describing mainstream comic art or comics in general, while the term “comix” is used specifically when speaking of underground (also known as alternative) comic art. Being an underground comix enthusiast I can’t help but notice the great similarities of Spiegelman’s work with that of Japanese alternative comic artists, those who produced work throughout the 70s -80s just like he did, such as Suehiro Maruo, Osamu Tezuka, or Katsuhiro Otomo. Later, during his talk, Spiegelman mentioned that throughout the phases in comic cultures, they all tend to look the same. As an homage to Charles Schulz “Peanuts” he drew, “Abstract Though is a Warm Puppy”, and he pinpointed how Charles Schulz’ work became some of pop culture’s most iconic artifacts.

Art Spiegelman, “Abstract Thought is a Warm Puppy”, The New Yorker, February 2000. Photo: Joséphine Mwanvua

Art Spiegelman, “Abstract Thought is a Warm Puppy”, The New Yorker, February 2000. Photo: Joséphine Mwanvua

During the talk, Spiegelman – who happens to have a very metaphorical way of speaking, and who is just as funny as his comics- sat comfortably, talking with the host, AGO’s Director and CEO, Matthew Teitelbaum about how the culture of comics changed society’s relationship to media. He remembered the early phase in the 60’s when comics were wordless and relief printed with woodcut pieces. He mostly spoke about what art means to him and his anxious battles with modernism, and whether comic books are art. He gave very long answers to Teitelbaum’s short questions, that contained a multitude of issues and stories. It was very interesting to hear him speak about how comics are treated nowadays: that comics can now be seen in museums next to Picasso, or studied in classrooms. This is highly unusual for this type of culture because, Spiegelman says, comic culture has a different energy than high class culture, what are originally, and essentially, collector’s items.

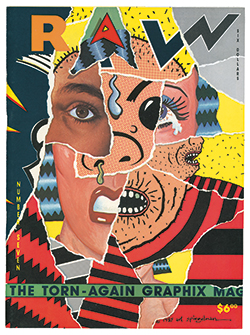

Art Spiegelman, “RAW no.7, The Torn-Again Graphix Magazine”, 1985. Courtesy of AGO.

Art Spiegelman, “RAW no.7, The Torn-Again Graphix Magazine”, 1985. Courtesy of AGO.

It’s true: comics, especially alternative comix, sit lower in the hierarchy of cultural class. It’s not regarded in the same way as ballet, the opera or classical music. The hobby of comic book collecting has always been seen as “nerdy”, or strange to a lot of those who don’t identify with that culture. However, although it’s still rather common to get negative reactions when we enthusiasts express our love for the hobby – comic book conventions have recently become mainstream. Take San Diego Comic Con for example: SDCC is the holy grail of all comic book conventions, and since last year, it’s been deemed as “mainstream” and gets a lot of attention in the media. Let’s not forget the fact that some of Hollywood’s biggest box office titles as of late are movies based on Marvel and DC comics. A lot of the people who attend these screenings are those who have never picked up a comic book in their lives and who even might have made fun of that kid in school who did.

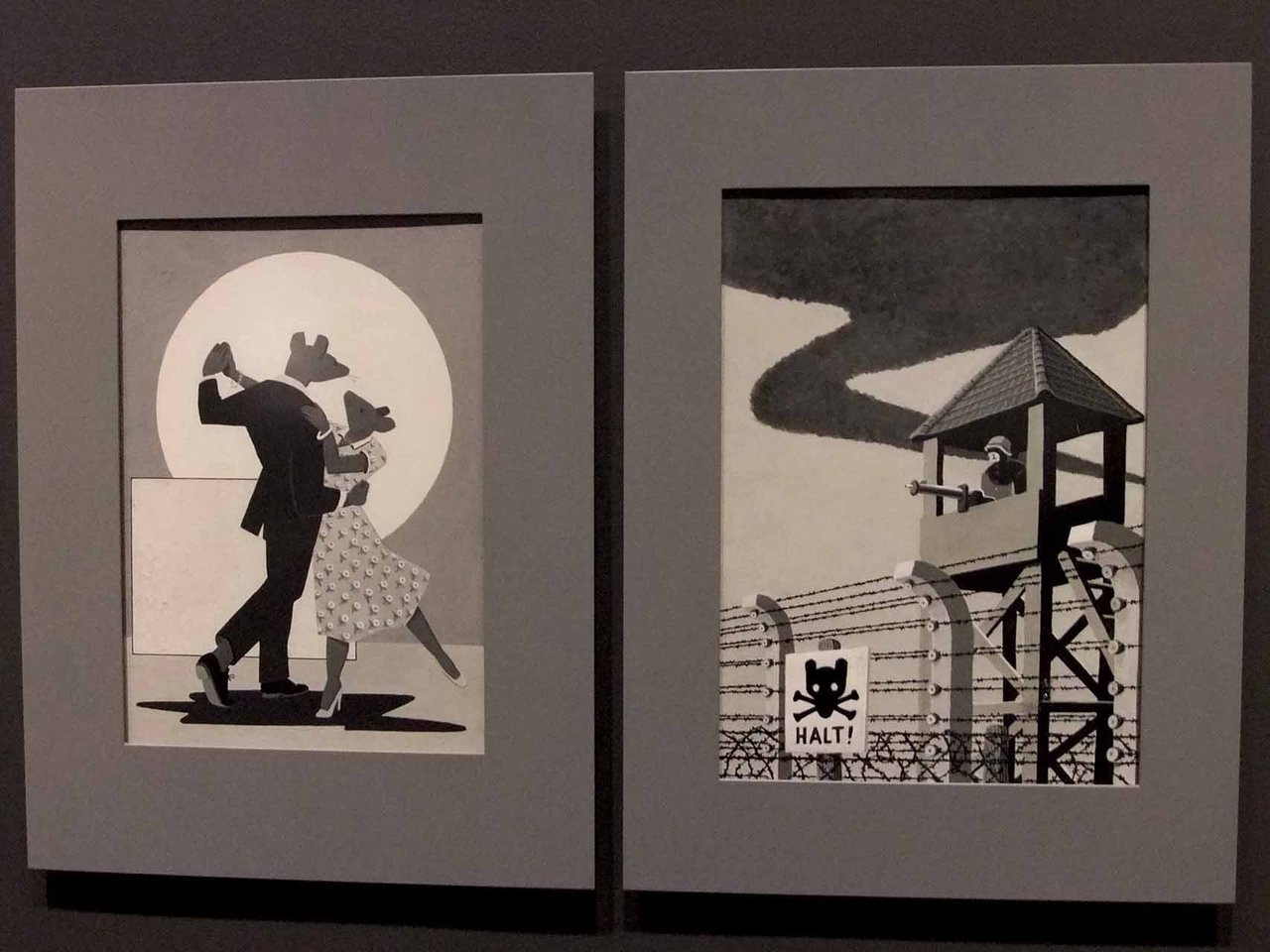

Art Spiegelman, contents pages of “Maus 1”, gouache and ink on paper, 1986; contents pages of “Maus II”, gouache on paper, 1991. Photo: Joséphine Mwanvua

Art Spiegelman, contents pages of “Maus 1”, gouache and ink on paper, 1986; contents pages of “Maus II”, gouache on paper, 1991. Photo: Joséphine Mwanvua

Then Teitelbaum, asked Spiegelman to talk about “Maus”, his most praised work to date. The artist spoke about the inspiration behind it: the Jewish identity, and his ambitions at the time, which were in line with the fact that he was turning 30 and going to “become an adult”. He states that the idea came from wanting to depict anthropomorphic animals, and creating a comic in the form of a bedtime story that told the tale of his parents’ experiences in Auschwitz. He also wanted to make a comic that was long enough to need a bookmark – Spiegelman wasn’t familiar with the idea of graphic novels yet.

I haven’t had enough of his comics history lessons yet; I’m going to see Art Spiegelman give another talk, “What the %@&*! Happened to Comics?”, at Bloor Hot Docs Cinema on January 26, 2015, where he will school the audience on the chronological history of comic art and the importance of it as a medium.

Joséphine Mwanvua

*Exhibition information: December 17 – March 15, 2015, Art Gallery of Ontario, 317 Dundas Street West, Toronto. Gallery hours: Tue & Thur – Sun: 10 – 5:30, Wed 10 – 8:30 p.m.