Histories of Art, a group exhibition currently on display at Daniel Faria Gallery, offers visitors an incredibly considered, delightfully irreverent, and often sassy take on art history. Comprised of work by four of the gallery’s artists — Shannon Bool, Chris Curreri, Mark Lewis, and Elizabeth Zvonar — the show confronts some of the prominent figures, discourses, and systems of representation that have crystallized over several hundred years into the art historical canon we all know and love (or at least love to hate). And through this confrontation, the show provides a scrutinizing and often very human slant on a discipline that can often be rather dusty, privileged, and overly academic.

Installation view at Daniel Faria Gallery, 2016, Histories of Art

Installation view at Daniel Faria Gallery, 2016, Histories of Art

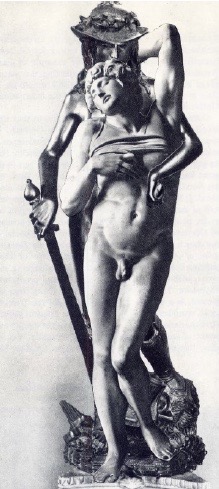

Approaching the subject from the sassier angle, Chris Curreri’s photographs portray revered sculptural subjects in states of indelicate discomposure. Taken by Curreri during a tour of the Art Gallery of Ontario’s conservation lab, the images show two statues — Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Corpus and Jacobus Agnesius’ St. Sebastian — in the midst of conservation work. As a result, the sacral plinths and mounts on which we ordinarily see these works displayed have been traded for conservator’s equipment. The statues lie prostrate, their finely carved limbs spread across roughly hewn fabrics, bent over triangular slabs of inert polyethylene, legs bound by unbleached cotton twill tape. By exposing the statues thus indisposed, Curreri reveals moments in the lives of artworks that are ordinarily conducted behind closed doors. He also underscores the permeability of these objects, which, though made of seemingly stable bronze or ivory are, like all material things, subject to the laws of change and decay. The effect is one of peering into the secret lives of these figures, which require cleaning and maintenance like all matter, indeed like humans.

Chris Curreri, Corpus (face), 2015, chromogenic print, 20″ x 27″

Chris Curreri, Corpus (face), 2015, chromogenic print, 20″ x 27″

Of course, this voyeuristic sense is heightened by the titillatingly immodest poses Curreri captures his figures in—poses which emphasize the erotic, even sado-masochistic tendencies of these and similar works. Through Curreri’s lens, the figures’ states of agony and sorrow transform into those of pain/pleasure. And such a treatment is not inappropriate to either figure: the eroticization of St. Sebastian bears its own history in art and literature, aided by writers like Thomas Mann and T.S. Eliot, while the erotic lineage of depictions of Christ has been explored by art historians like Leo Steinberg since at least the 1980s. At Daniel Faria, Curreri takes up both of these dialogues, addressing the sexually ecstatic undercurrents of much early Modern religious art. Yet, as in the rest of his practice, he also proves that the truths of objects lie in their broader contexts and their interactions with ideas, bodies and other objects. Whether situating the figures in their museological context or in their cultural one, in Curreri’s photographs, the two statues are very much part of and defined by the world they inhabit.

Chris Curreri, St. Sebastian, 2015, chromogenic print, 26.25″ x 34.5″

Chris Curreri, St. Sebastian, 2015, chromogenic print, 26.25″ x 34.5″

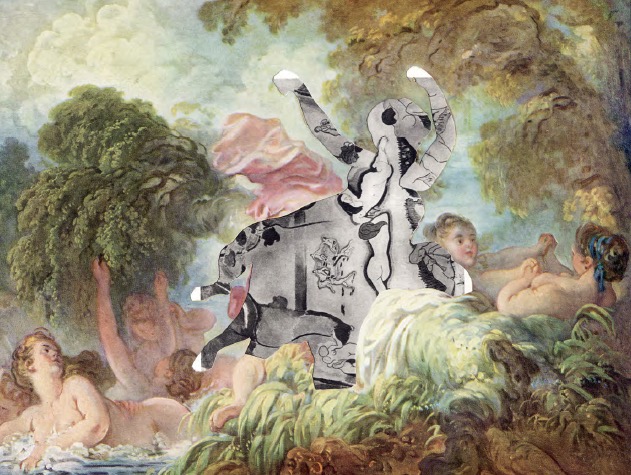

Elizabeth Zvonar’s “History of Art” (2009) also engages the contexts of artworks, though in her case, the context is of a more discursive nature. Through a series of collages and small-scale ceramic sculptures, Zvonar takes on H.W. Janson’s iconic History of Art, a text used for decades as the go-to survey of art history and one also instrumental in constructing the art historical canon. In an irreverent act of reappropriation, Zvonar cuts up and collages the text’s pages into often ironic, often cheeky, and always poignant new images. Artistic subjects from vastly different art historical periods and in varying styles meet and interact, spotlighting historical consistencies and disjunctures. Matisse’s bathers meet Fragonard’s, for example. Or Rodin’s’ “Thinker” coddles an earlier version of a similar subject.

Elizabeth Zvonar, Dancing Bathers French, 2009, collage, 9.25″ x 7.5″

Elizabeth Zvonar, Dancing Bathers French, 2009, collage, 9.25″ x 7.5″

In all instances, Zvonar adds new meaning to the originals. Like Curreri, Zvonar underscores erotic currents within iconic works, for instance, as in her combination of Donatello’s bronze David with one of Michelangelo’s Slaves. Or, she uses visual layering to comment on acts of violence and war, as in “The Blind Leading the Third of May.” At her most serious, Zvonar’s visual juxtapositions call attention to the gaps, hypocrisies, and misogynies within art’s historicization. The most blatant example is her collaging of Janson’s title page with Giambologna’s “Rape of the Sabine Women” in her not-so-subtly titled “History of Art/Women Get Raped.” This scathing visual critique builds on much of the criticism the text has received since its first edition, which noticeably excluded women artists but was unsparing in its inclusion of the female nude.

Elizabeth Zvonar, Undying Love, 2009, collage, 3.5″ x 7.5″

Elizabeth Zvonar, Undying Love, 2009, collage, 3.5″ x 7.5″

Elizabeth Zvonar, The Blind Leading the Third of May, 2009, collage, 9.5″ x 6″

Elizabeth Zvonar, The Blind Leading the Third of May, 2009, collage, 9.5″ x 6″

Zvonar’s porcelain works also draw on Janson’s text in a way that is perhaps even more playful — though certainly still as irreverent—as these collage works. Each sculpture reenacts one of the book’s most iconic paintings — with one catch. In place of figures, Zvonar has rendered the scenes using white slip casts of her own index finger. The results are whimsical and delightfully bizarre: groups of fingers coalesce into the sea-weary figures of Gericault’s “Raft of the Medusa,” for instance, or congregate like partygoers at Titian’s “Bacchanal of the Andrians.”

As the curatorial text for the show notes, Zvonar’s choice of the index finger is a nod toward its significance — and the significance of the gesture of pointing — within the visual canon of art history. Think Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling or Plato’s gesture skyward in Raphael’s The School of Athens. Yet, it also serves to eroticize these iconic works, bringing them into the realm of touch and the body. Indeed, taken as a collective, it’s hard to ignore the sculptures’ writhing sexuality. As in her collage works, this serves to expose the blatant eroticism — with its often-misogynistic undertones — of much of the artistic canon. But the fingers also brings the original works into the realm of the surreal, perhaps calling to mind Eugène Atget’s dismantled mannequins or Georges Bataille’s 1929 photograph “Big Toe.” The effect is to render the original images as more than slightly ridiculous — Zvonar literally gives the finger to some of art history’s most famous (male-generated) works.

Elizabeth Zvonar, Raft of the Medusa (After Gericault), 2009, porcelain, 9″ x 7″ x 5″

Elizabeth Zvonar, Raft of the Medusa (After Gericault), 2009, porcelain, 9″ x 7″ x 5″

In a similar act of cooptation, Shannon Bool’s “MEC V” (2015), part of her ongoing “Madonna Extraction” series, similarly appropriates and manipulates historic works — in this case Jan van Eyck’s “Madonna and Child Enthroned,” circa 1436, and Petrus Christus’ “Virgin and Child Enthroned” from 1458. Yet, more than Curreri and Zvonar, Bool uses this cooptation to directly address historical and contemporary systems and processes of visual representation. To do so, Bool extracts from the original paintings the strikingly similar carpets each artist laid beneath his figures’ feet—carpets utilized by Agnesius and Christus to aide in the creation of visual perspective and display technical mastery. Bool then isolates these carpets and brings them together, replacing their surrounding scenes with a grey-and-white Photoshop grid. This new image is then fixed as an actual carpet woven by Anatolian weavers and displayed flat on the gallery floor.

Shannon Bool, MEC V, 2015, wool, 106″ x 66.5″

Shannon Bool, MEC V, 2015, wool, 106″ x 66.5″

The result of this process is a layering of ontologies, visual effects, states of refinement, and artistic processes into one object. What were once representations of carpets are now an actual carpet, for instance. And this carpet’s flatness—along with the flat grey-and-white grid—contrasts markedly with the original images, whose visual depths are partially nullified by their display on a flat ground. Further, Bool has taken what is ordinarily a temporary state—a moment of digital editing—and fixed it into a state of permanence, converting highly refined objects (the original paintings) into a sort of rough edit, and then into another highly refined object (the finished carpet). And all the while, she contrasts modern techniques of digital representation and manipulation with an early visual system requiring very different artistic processes and forms of technical mastery. It is a dizzyingly complex and impressive maneuver—one that looks head on at the ways we see and have seen works of visual art today and almost 600 years ago.

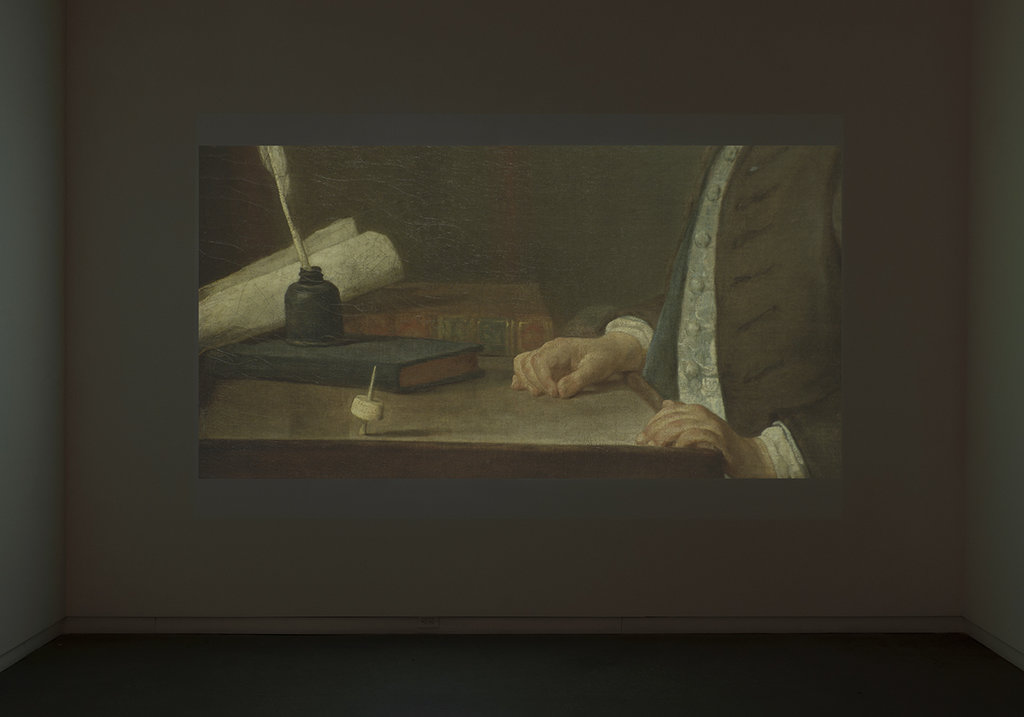

In a similar move, Mark Lewis also looks at systems of representation and viewing, contrasting the depiction of movement in early Modern painting with its depiction on film. In “Boy with a Spinning Top (Auguste Gabriel Godefroy)” (2014), Lewis films Chardin’s painting of the same name, capturing in moving images a still work that seeks to demonstrate motion within a single frame. Lewis thus calls attention to the varying learned and culturally embedded visual cues that we as viewers use to read movement within different types of media—cues like Chardin’s impossibly suspended top, for instance; or the changing size of objects on film, which read as changes in distance to the camera. Comprised of one long shot taken mostly at close range to the painting, the film also encourages the type of prolonged, intimate looking that we so rarely do in the gallery setting. Yet, in moving from this extended close-up to a broader angle, Lewis also connects Chardin’s work to its museological context within the Louvre. He situates the painting first within its frame, and then on the wall beside its accompanying curatorial label, and finally as part of a row of neighbouring works. In this way, the film parallels the works of the other artists within the show, who play with context in order to make statements about the shifting meanings of historic works of art or, indeed, objects in general.

Mark Lewis, Boy With a Spinning Top (Auguste Gabriel Godefroy), 2014, 5K transferred to 2K, 4 min., 39 sec.

Mark Lewis, Boy With a Spinning Top (Auguste Gabriel Godefroy), 2014, 5K transferred to 2K, 4 min., 39 sec.

Mark Lewis, Boy With a Spinning Top (Auguste Gabriel Godefroy), 2014, 5K transferred to 2K, 4 min., 39 sec.

Mark Lewis, Boy With a Spinning Top (Auguste Gabriel Godefroy), 2014, 5K transferred to 2K, 4 min., 39 sec.

This latter parallel hints at what is strongest about the show: each work is unique, approaching the history of art from a drastically individualized perspective. Yet, the common threads are incredibly strong and run deeper than a simple shared interest. Each of the four artists engages deeply and subtly with art historical conversations: they confront injustices, point out erasures, and probe entire modes of seeing. And all of it is done intelligently and often with a sense of humour. For a discipline often accused of taking itself too seriously, this seems to me the best we could ask for.

Catherine MacArthur Falls

Images are courtesy of Daniel Faria Gallery.

*Exhibition information: Histories of Art – a group show by Shannon Bool, Chris Curreri, Mark Lewis, and Elizabeth Zvonar, February 11 – March 26, 2016. 188 St. Helen’s Avenue, Toronto, M6H 4A1. Gallery Hours: Tue – Fri, 11 – 6; Sat, 10 – 6 pm.