This year marks the fair’s 19th year and with an incredible 102 exhibitors showcasing their collections of a vast assortment of modern and contemporary art for audiences and patrons to enjoy.

The title INDOOR/OUTDOOR (Focus: California) seems evocative of the text The Culture of Nature (1992) by Alexander Wilson, who describes how humans, through the advent of the ‘home’, have created a dichotomy of the indoor and outdoor space. This notion is expanded to become a complete “Othering” of natural phenomenon and a false hierarchical position of human beings above nature.

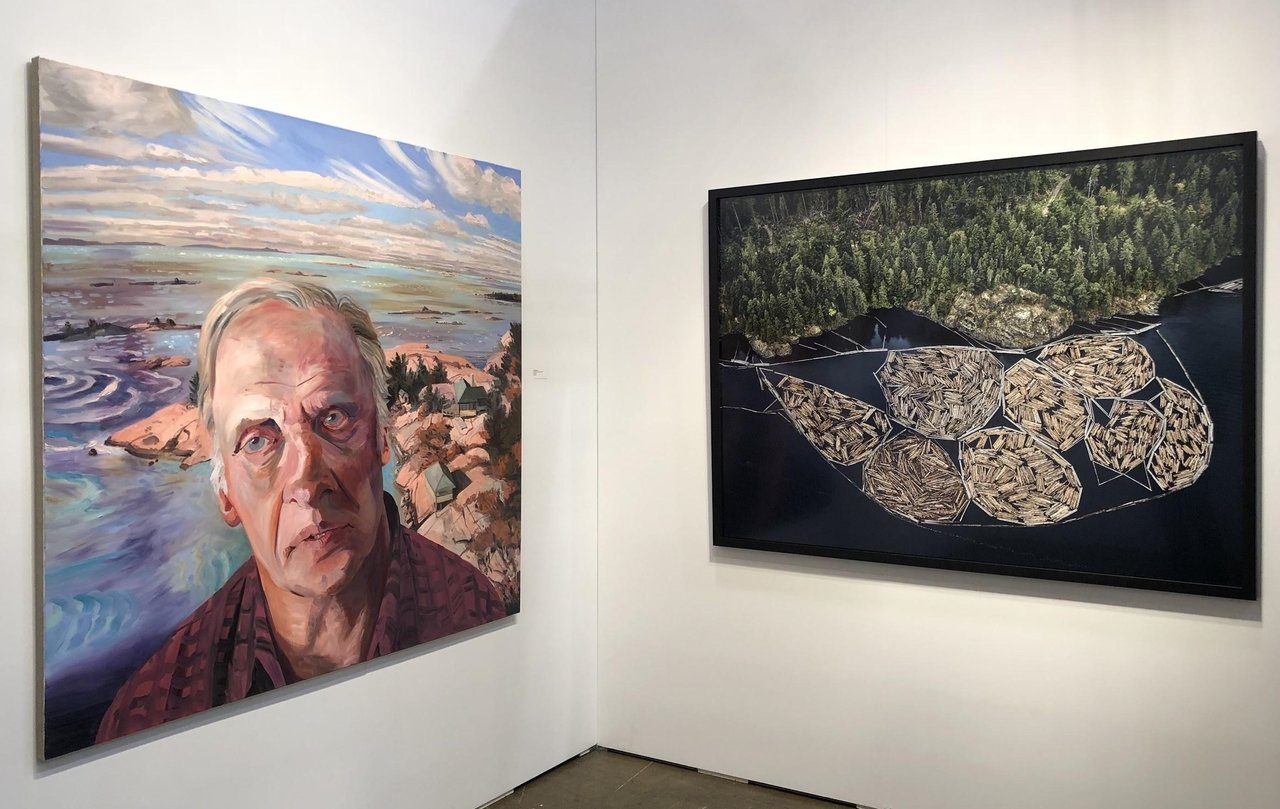

John Hartman, Ian Brown, Go Home Bay 2017 (left) and Edward Burtynsky, Log Booms #1 (right)

Taking this idea further, the concept of the Anthropocene is relevant in interpreting the themes and concerns emphasized throughout the fair. The meaning of the term is the proposed title for the current period of time where humanity has eclipsed all other forces in effecting the climate and geography of the planet. These notions of the subjugation of nature have deep and critical connections to consumer culture, ecological catastrophe and violent histories of segregation, which many artists have addressed in their artworks.

Froot Loops Fun Size #4 and New York Times Arts & Leisure 12-17-17, 2018 by Paul Rousso

Further theoretical frameworks that influenced my reading of Art Toronto include John Berger’s seminal text About Looking, especially a chapter titled, “Why Look at Animals?”. It points out the inverse relationship between the disappearance of animals and their increased representations in art. People create more and more simulations of nature as that very nature is disappearing.

Suné Woods in From Here We Go Nowhere collaged together pieces of crumpled magazine pages that picture idyllic water bodies, devoid of human presence or interference as an environment of immense beauty and calmness but also a symbol of racism. Pools, beaches and fountains were significant attractions in the mid-20th century that were intentionally segregated because of the white myths of contamination. The crumpling of landscapes seems to reject the original meaning of simplicity and replaces it with a new landscape of chaotic complexity.

From Here We Go Nowhere 2015 by Suné Woods

In Kent Monkman’s Washing Mary’s Tears, we see a contemporary event of police violence against Indigenous women. Three faceless and heavily armed policemen point their weapons at an already subdued woman writhing in pain, while two other women attempt to aid her, washing over her tears caused by pepper spray. The scene is potentially about the Standing Rock protests the DAPL Pipeline, and illustrates an extremely tragic time for environmental, Indigenous and human rights. This scene is also an allegory for the forced reliance on capitalist products, such as bottled water, because the hegemonic powers have crippled the very natural resources that the people in the painting are trying to protect. The work is highly effective and technically brilliant, with the fear, injustice and pain emanating from the canvas.

Kent Monkman, Washing Mary’s Tears, 2018 at the Pierre-Francois Ouellete Art Contemporain

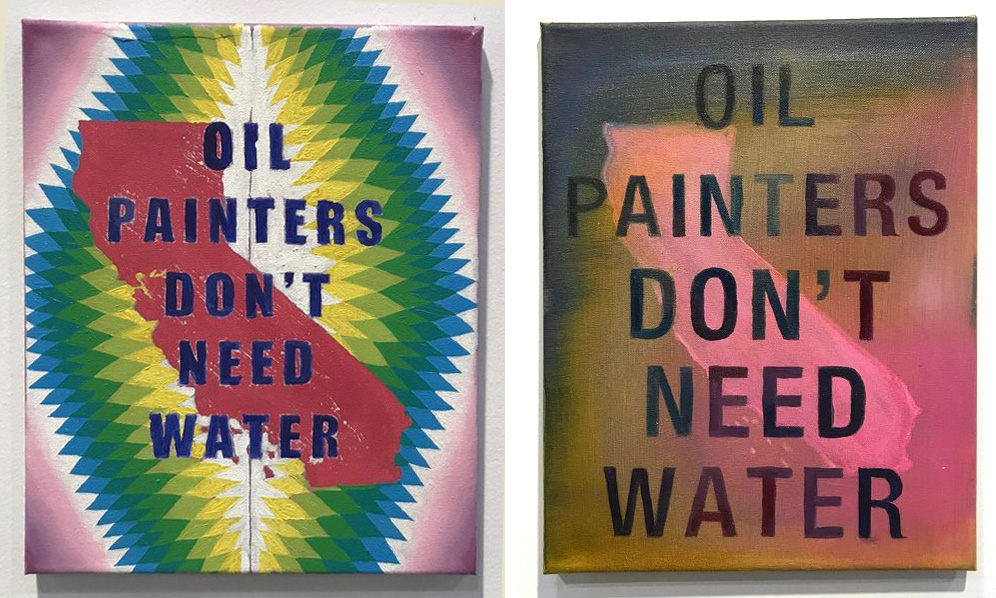

Christine Wang’s series (from Focus: California) use stenciled writing that reads “OIL PAINTERS DON’T NEED WATER” overlaid by a map of California. The work is a joke or a cynical statement, as oil paint is not water soluble, but also addresses the looming fear of drought and water-shortage in California.

Christine Wang, California Painting #6 (left) and California Painting #15 (right)

In David Drebin’s Blue Dream, we see a deep blue sea and an inground swimming pool with a single figure swimming in it. This choice of an artificial environment over the natural one, just metres away from each other, yet maintaining the need for a distinction, shows humanity’s need for control. Unlike Drebin’s piece where a single isolated figure illustrates humanity’s greed, in Joshua Jensen-Nagle’s Strength in Memories we are reminded of our competition over nature. The photo is an aerial view of a beach where identical umbrellas crowd the shoreline, turning it into suburbia, homogenic and dense.

David Drebin, Blue Dream, 2018, detail (left) and Joshua Jensen-Nagle Strength in Memories, 2017 at the Galerie de Bellefeuille (right)

Bathed in a deep blue up to the figure’s chin and surrounded by floating debris, Willy Verginer’s wooden sculpture Dumbries tl ega is a powerful statement about water pollution and how consumer capitalism is directly corrupting even the most innocent or nostalgic experiences of swimming in a lake as a child.

Willy Verginer, Dumbries tl ega, 2018, Zamack Contemporary, Tel Aviv

The swimmer is a recurring character throughout Art Toronto. The underwater imagery of headless bodies hidden by the reflection of light against the surface of the water and the inverted depictions of just a torso and head emerging from the water in quiet moments of relaxation recur within different mediums, galleries and by very different artists. This trend could be a sense of escapism into the mysterious and cleansing water, or an exploration of advancements in technology that make underwater photography more accessible, or perhaps it is a farewell to a time when water was plentiful and leisurely.

Sage Szkabarnicki-Stuart, Urban Bath at Gibson Gallery

Larry Sultan, Untitled from The Swimmers (1978-1982)

Guy Lavigueur’s L’Homme (Man) shows a birds-eye view of a lake with the appearance of a natural formation that resembles a human body, with its head as a small rounded peninsula. The work can be read as some mythological, god-like figure emerging from the ground around the lake, or simply as the prehistoric parts of our brain projecting or searching for images of ourselves or predators in everything around us, a phenomenon known as pareidolia. The work could also be a reminder that humanity and landscape are deeply entangled and shape each other.

Guy Lavigueur’s Series Unprotected L’Homme (Man)

The photograph, Immolation, by Judy Chicago was taken back in 1972, however it seems as if it was taken today. Originally created during a time when Buddhist monks were self-immolating to protest the Vietnam war, and when the artist was researching the Indian cultural and mythic practice of widows throwing themselves into funeral fires – now the work could to be a statement about the human body in an apocalyptic time of desolation.

Judy Chicago, Immolation, 1972; from Woman and Smoke. Printed 2018

Still – Framed by Max Dean was a large, central installation. One of only a few mechanic new media projects at the fair, the work included a moving screen that produces a bubbly film from soapy water, as well as mannequins with active smartphones used to submit selfies to a live Instagram feed online. The work is very complex and the meaning behind it seems both poignant and superficial depending on how you unpack its process and conceptual framework. The installation seems post-ironic, mocking both participants and itself with its flagrant description and the vapid narcissism associated with selfie culture.

Still – Framed (2018) by Max Dean

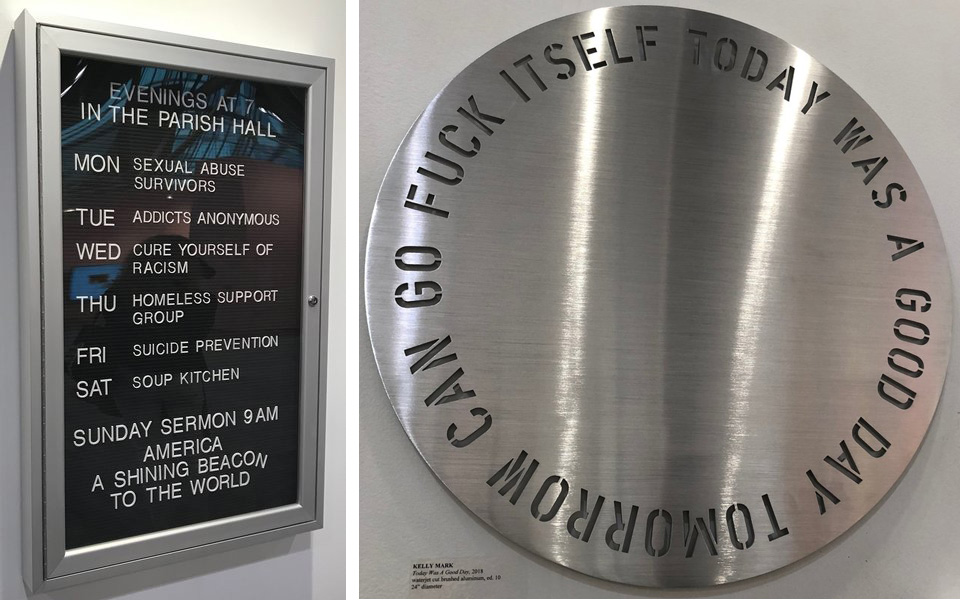

Despair and cynicism have always held a special place in the arts and culture realms, works such as Erika Rothenberg’s America A Shining Beacon and Kelly Mark’s Today Was A Good Day, demonstrate a contemporary ethos of pessimism and rejection of false ideals of hope.

Erika Rothenberg’s America A Shining Beacon (left) and Kelly Mark’s Today Was A Good Day, 2018 (right)

Many other works demonstrated the cruelty of nature and our companion species in the current age of scarcity and technological acceleration. The Edge of Chaos by Nicholas Crombach appears to be a glimpse into the mind of a domesticated pet dog that imagines his play with his toys as a violent hunting of a deer with his pack mates, when in fact he has been domesticated and bred to be a harmless accessory to a home.

The Edge of the Chase, 2018 by Nicholas Crombach

Overall, the Art Toronto 2018 show was spectacular and robust with crowds gathering at nearly every booth and red dots denoting sales scattered beside countless placards. The gallerists were friendly, the curators were knowledgeable, and the art was beautiful and meaningful in so many new and thoughtful ways.

Text and photo: Nathan Flint