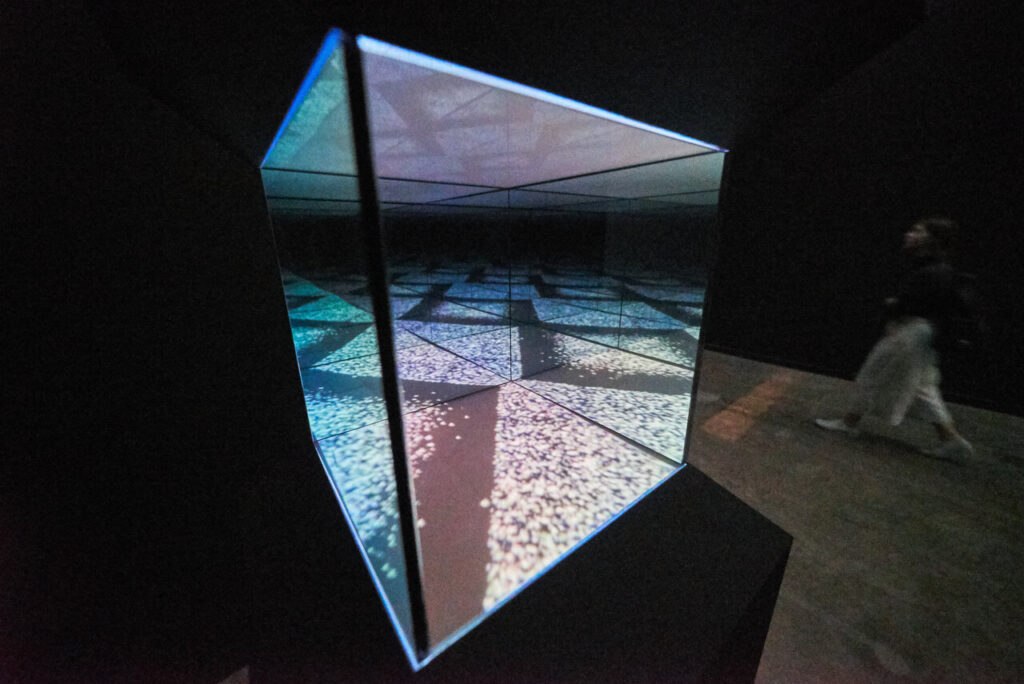

Behind a heavy curtain in the spacious Arsenal Contemporary Art lies a set of six video installations titled Kali Yuga. The phrase refers to a Hindu myth and translates from Sanskrit as the ‘Age of Vice’. Its creator, Tasman Richardson, is a Toronto-based media artist who exhibits internationally. The Vedic myth offers a version of the theory that the world is cyclical, that is, characterised by an unending process of creation and destruction. Our current age is the last, at which point the creator awakens from a dream state and thereby brings about the end of the world. It is an age defined by degeneration and corruption. The one sin of ours that Richardson focuses on especially is the obsession with the self, i.e., narcissicism.

Tasman Richardson, Ouroboros, 2019, Digital8 camcorders, projectors, Arduino robotic pieces, custom code, speakers, MacBook, external audio interface, wood, plastic, Variable dimensions

A parallel is drawn between this mythical age and our era of technological disruption. Here Richardson points to the writings of such luminaries as J.G. Ballard and Aldous Huxley, and their literary predictions of a dystopian future. According to both these authors the rise of technologically fueled capitalism leads to the deadening of our emotions, as our lives become increasingly banal. For Ballard one possible effect of this is to become sexually aroused by machines – cars in particular. This idea is explored in his famous novel Crash, where the protagonists gain their thrills by seeking out the immediate aftermaths of violent car crashes. He understands capitalism as tapping into our latent death drive.

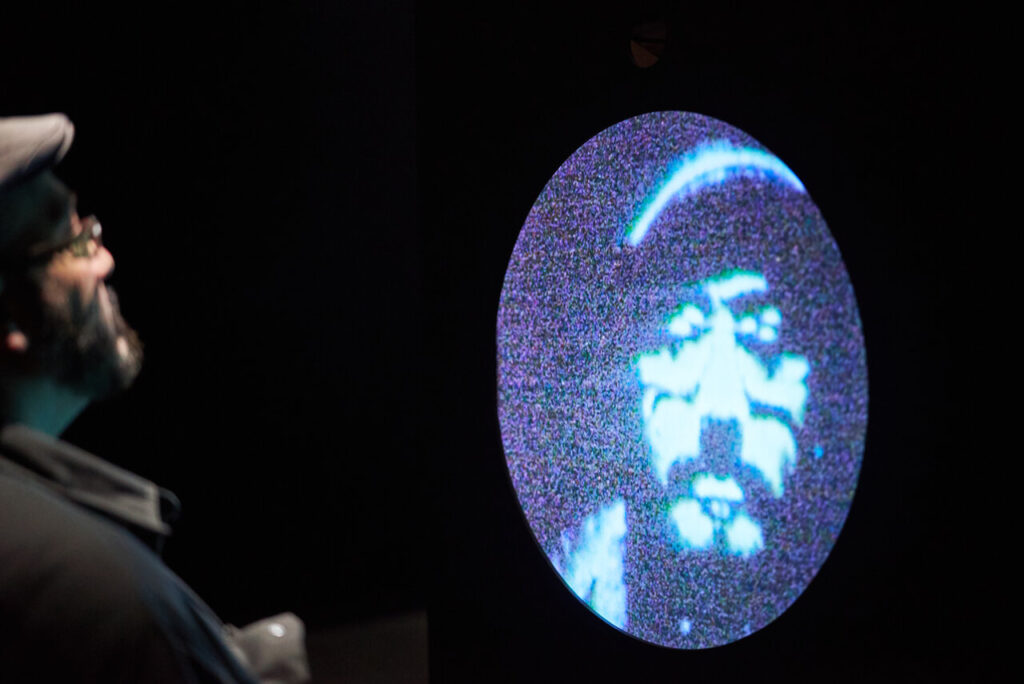

He sees technology as conspiring to make us spectators of our selves. Society is transforming into a virtual panopticon, where we act as both the inmates being observed and the guards observing. Our online lives have made us both ‘voyeurist and exhibitionist’, as Richardson puts it. This duality is directly addressed in his installation titled ‘Sphere of Influence, Circle of Protection’. You enter a space to be surrounded by screens projecting crashes filmed on dash cams. These images originate from postings of the video footage online. Why would anyone wish to share such traumatic imagery online? It is, curator Shauna Jean Doherty suggests, an extension of “our willingness to report constantly on our own location, consumer habits, and demographic information often in exchange for a free wifi signal – that connects us to a system that feeds off of an insatiable need it has manufactured.”

Tasman Richardson, Sphere of Influence, Circle of Protection, 2015-2019, Video multiplier, projectors, broken mirrors, camera strobe flash, midi to voltage converter, speakers, MacBook, external audio interface, wood, cloth, paint, Variable dimensions

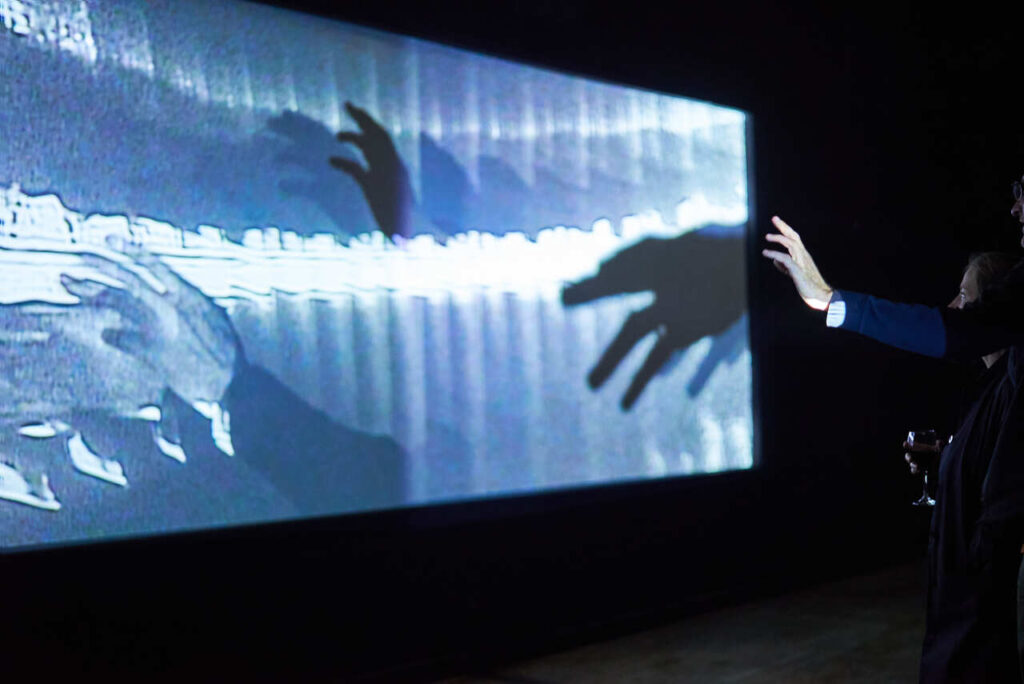

Technology, it is implied, is leading to a sort of obliteration of the self. This idea is illustrated by his installation ‘The Cave’. It consists of the silhouette of an amorous couple behind which are a series of receding and increasingly degenerate video projections of themselves, which is the result of their projecting a video recording of their last sexual encounter each time they meet. By observing themselves observing themselves and so on, they ‘shift from self to object’. Slats placed in front of this video display put the gallery viewers in the position of voyeur, making them conscious of trying to spy on the scene through the gaps. The lovers on the screen too are voyeurs, that is, of what used to be themselves.

Tasman Richardson, The Cave, 2019, Caméscope VHS, magnétoscope, projecteur à portée ultra courte, matelas, haut-parleurs, MacBook, cable DVI-I vers HDMI, bois, peinture / VHS camcorder, VCR, ultra short throw projector, mattress, speakers, MacBook, DVI-I to HDMI cable, wood, paint

The installation ‘Fire and Theft’ is inspired by the myth of Prometheus who, having stolen fire from the gods and given it to humans, is cruelly punished. His fate is to be chained to a rock and have his liver pecked out. The liver immediately regenerates to be pecked out again the next day ad infinitum. What you see is a panoramic surround of screens projecting scenes of the rising and setting of the sun at various points on the earth. If you were to stand there for a few hours, we are told, you would see this phenomenon from the convenience of one spot. We have effectively captured the sun. The power of technology corrupts us. Our technologically inspired hubris is condemning us.

Tasman Richardson, Fire and Theft, 2009, Live EarthCam, Mac mini, projectors, wood, cloth, paint, Google Chrome plugins, Variable dimensions

All these ideas are explained in the exhibition catalogue, without which the viewer is largely at sea. It is striking how Freudian these themes are – narcissicism, the death and life instincts. Richardson’s assumption appears to be that technologies such as social media foster these Freudian instincts and pathologies, and that this is a threat to civilisation. But there is little evidence that we are becoming more pathologically narcissistic for example. Most of us remain psychologically balanced over all.

Tasman Richardson, Going Gray, 2019, Digital8 camcorders, CRT televisions, RCA to RF convertors, 4K flat screen, HD camcorder, live optical rescan, wood, paint, glass mirror, Variable dimensions

Richardson is clearly intellectually ‘aroused’ by the idea of our collective death, that is, the apocalyptic end of our society. It is more exciting to believe that we live at the dramatic close of history rather than somewhere on its continuum. To be charitable, there’s no doubt that technology is revolutionising how we interact with one another, and many of the changes are troubling. The drama of dystopian fictional visions like Ballard’s is a useful device to point out how troubling they are, even if they don’t in themselves spell the end of civilisation or some comprehensively hellish future.

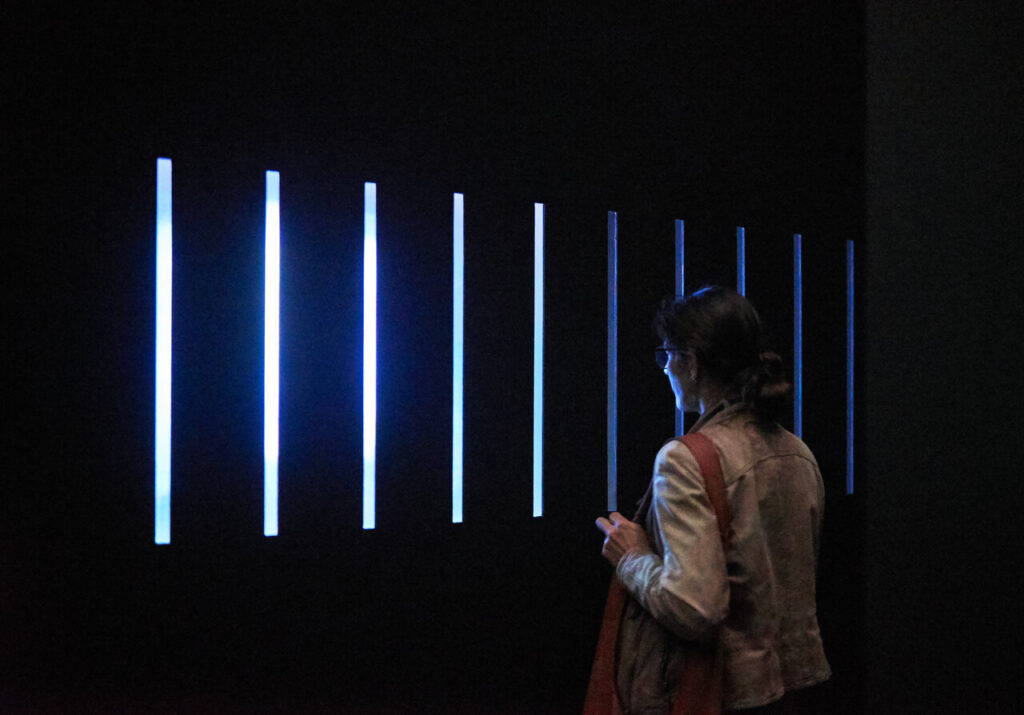

Nihilistic forebodings aside, Richardson is a master of technological aesthetics. Walking into the installation ‘Sands Stand Still’ for example, you peer through surveillance mirrors into a box that is sporadically bombarded by cathode rays. This produces specks of light that are endlessly reflected out in every direction by the mirrored walls. The illuminations are converted into an accompanying hypnotic soundscape. The effect is mesmerising.

Tasman Richardson, Sands Stand Still, 2017-2019, Glass surveillance mirror, wood, paint, micro projectors, DullTech media players, induction sound, CRT static, vellum, speakers, aircraft cable, Variable dimensions

Hugh Alcock

Images are courtesy of Arsenal Contemporary Art. Photo credit: Romain Guilbault

*Exhibition information: Tasman Richardson: Kali Yuga, March 9 – May 22, 2021, Arsenal Contemporary Art, 45 Ernest Avenue, Toronto, please book your visit.