Clint Roenisch Gallery has put on a group show titled The Thawing of the Great Bear. The aim, as Roenisch describes it, is to present “a dialogue around transformation and flux, the mutability of myth across geographies, the maw of time and of geological forces, of the regenerative power of nature, of the passing down of wisdom…and of our tenuous place in the cosmos…” These are grand themes indeed. In terms of the works themselves, on display is a range of pieces from very different cultures. They roughly divide into two groups – native American artefacts (by west-coast and arctic peoples specifically) and works by local Ontario artists. They date from the mid – to late twentieth century up to the present. It is an eclectic mix, artfully arranged in one large room.

Installation view of The Thawing of the Great Bear at Clint Roenisch Gallery with Amos Kaganak (Scammon Bay, Alaska), Mask, carved and painted wood with applied fur; unique, 9 x 9 inches approx. (right)

On the far wall hangs an enhanced colour photograph of a nebula in the Carina constellation, though it is another constellation that is central to the show’s themes, namely Ursa Major. This constellation makes up part of what is known as the big dipper, that is, a configuration of stars in the northern sky that outlines of a plough, or frying pan. In classical mythology, the constellation itself has the shape of a she-bear (ursa) because it consists of one of Jupiter’s lovers, Callisto, who was transformed into a bear by his jealous wife, Juno, and later thrown out into the heavens by Jupiter in order to save her from being hunted by her own son who was unaware of her identity.

Dorian FitzGerald, The Eta Carinae Nebula, NGC 3372, 2010, archival light jet print, edition number 2 of 3, 48 x 96 inches

Other cultures share hunting myths around the big dipper that date back many millennia. The Alaskan Yup’ik people, for example, see the shape of a caribou. Often in ancient North American cultures these stars are understood to show a wounded bear or deer being pursued by hunters. Several of the native works depict hunters, e.g., Yup’ik Doll Made from a Bird (artist unknown) and Mannumi Shaqu’s acrylic painting Fox Hunter and Family. The subject matter is no accident in the sense that these far-northern peoples do not so much form hunter-gatherer societies as hunter societies, given the relative scarcity of vegetation in these regions.

Artist Unknown (Bethel, Alaska), Yup’ik Doll Made From A Bird (Standing Hunter with Harpoon and Gaff), hide and feathers of a willow ptarmigan, wooden implements; unique, late 20th century, 11 inches tall

Mannumi Shaqu (1917 – 2000), Cape Dorset / Kinngait, Fox Hunter And Family, c. 1975, acrylic on paper, 20 x 26 inches

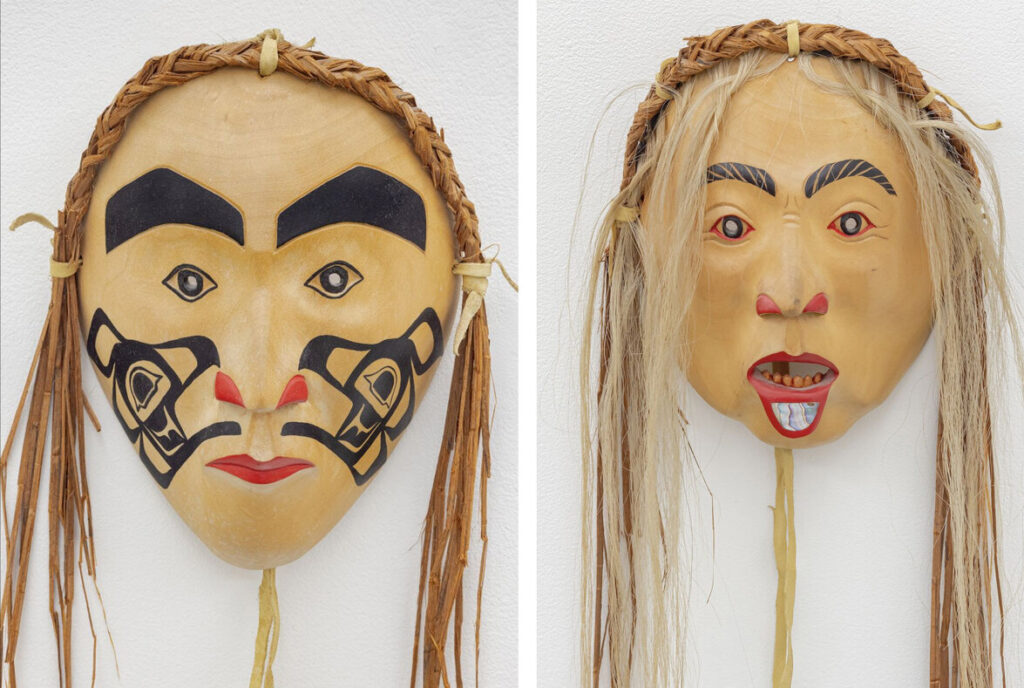

Roenisch explains that the masks on display originally played a strictly ceremonial role, so that when a ritual was over the mask was discarded. However, visitors from the south took interest in these artefacts as aesthetic objects. These artefacts soon became desirable items to collectors. Subsequently, many of these societies have developed artistic communities that supply this collectors’ market while attempting to promote and preserve their traditional hunting-based culture. There is an irony here in the sense that by making artefacts with the aim of showcasing their culture their culture is changed, since the original reasons for making the artefacts dissolves. This fact tallies with the show’s overall theme, namely the inherent mutability of the world and nature.

Artist Unknown (Bethel, Alaska), Spirit Mask, painted hide on woven basketry oval placket; unique, 11.5 x 9 inches (left) & Justus Mekiana (Anaktuvuk Pass, Alaska (1929 – 2009), Inuit Death Mask, caribou hide with fur trim, beard and eyebrows; unique, 10 x 8 inches approx. (right)

Stan Greene (b. 1953, Salish / Nez Perce), Eagle Crest Mask, alder, bark, paint; unique, 9 x 7 x 4 inches (left) & Old Lady With Labret, cedar, bark, hair, abalone inlay, paint; unique, 9.5 x 8 x 4 inches (right)

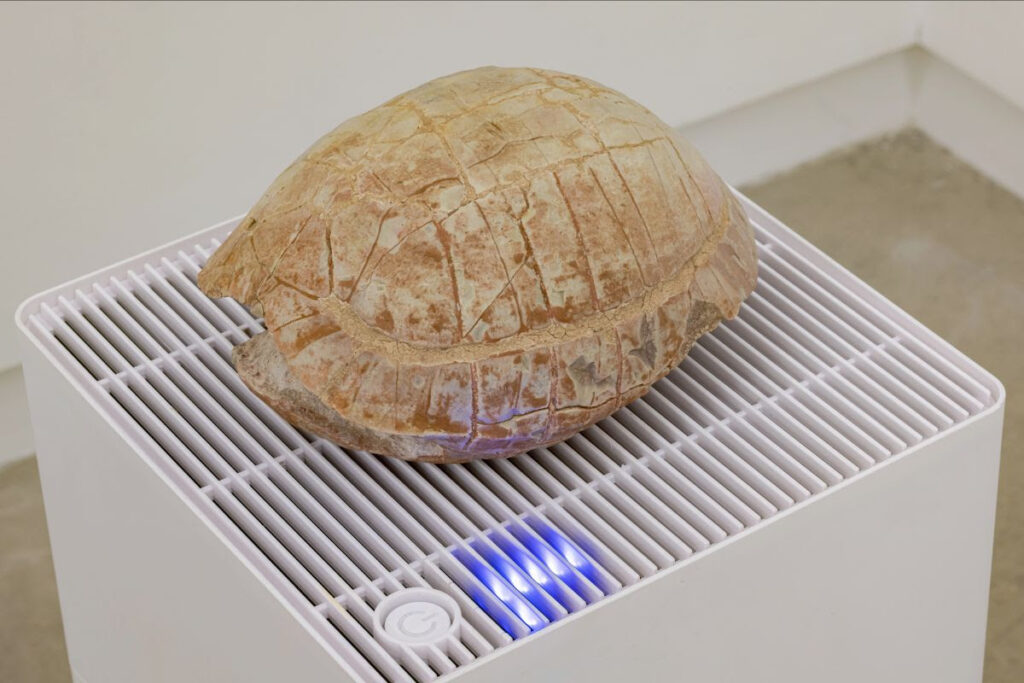

One of Jason de Haan’s works, Free and easy Wanderer (Yellow River), is a meditation on this theme. The work comprises a fossilised turtle carefully placed on top of a humidifier. De Haan notes that even something as seemingly permanent as a fossil is fugitive. It will react with the water in the atmosphere to incrementally dissolve and evaporate the minerals it is made of. So even this fossil is subject to change. Nothing lasts. Still, this idea of flux – call it Heracleitean – is itself somewhat paradoxical. For if everything is in constant state of flux then it seems impossible to detect change, for change can only be measured against those things that remain constant. One such constant is the stars. Ancient peoples all over the world thought of the firmament as eternal and outside of nature and temporality. That is why they imagined that casting characters like Callisto and hunted animal spirits into the heavens led to their permanence. Indeed, it is this permanent backdrop that enabled these peoples to pass on the stories of gods, spirits and hunters from generation to generation over thousands of years.

Jason de Haan, Free and Easy Wanderer (Yellow River), 2014, found fossil, humidifier (white), concrete, 12 x 10 x 17 inches (detail)

In general, themed group shows face two challenges. First, they can seem ad hoc, that is, invented in order to present what is in fact a disparate collection of works. The theme thus appears to be an afterthought. Second, they can make the artwork subservient to the curation. In other words, the artworks can sometimes be treated as props rather than showcased in their own right. I think Roenisch has avoided both these pitfalls.

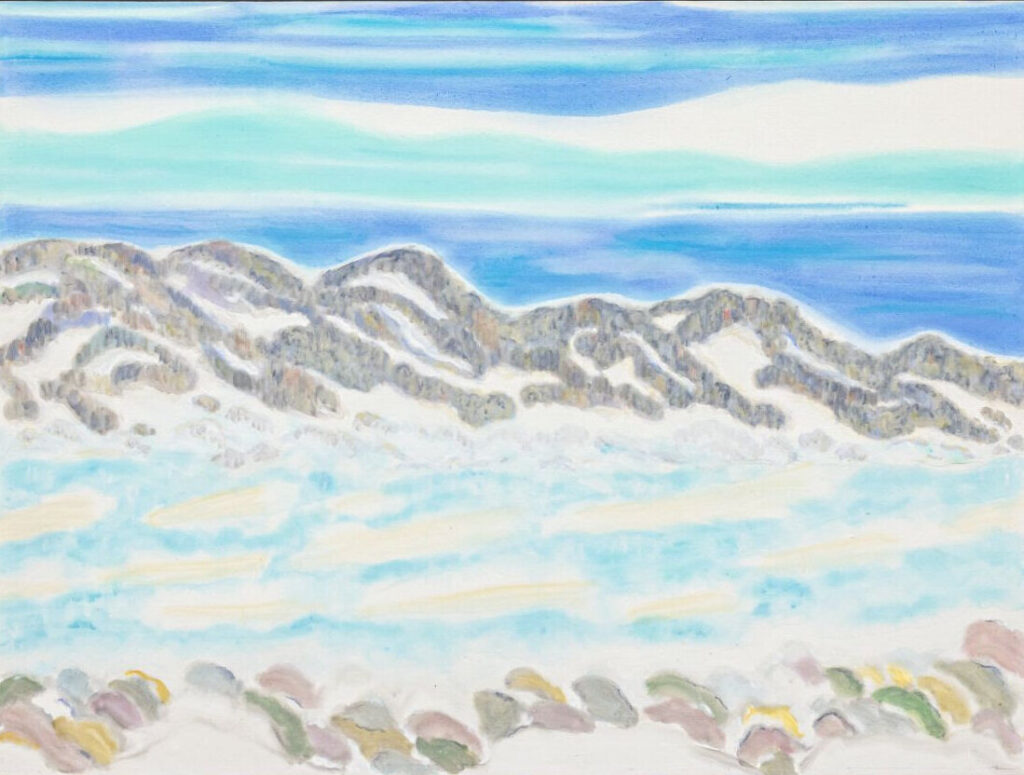

The themes span these two groups of works in various ways. For example, we have Toronto artist Kathleen Graham’s painting of an arctic landscape, Arctic Thaw in June. Roenisch tells me that on her visits to the arctic region Graham helped introduce the inuit to acrylic painting, offering a direct connection to Shaqu’s painting of the fox hunters which was done on a few years later.

Kathleen Margaret Graham (1932 – 2008), Arctic Thaw In June, 1990, acrylic on canvas, 60 x 80 inches

Others focus on the processes of making art and their links to geological forces of nature, e.g., Niall McClelland’s untitled work that consist in a canvas that has been scraped and dragged on the ground before being painted.

Installation view with Niall McClelland, Untitled, mixed media on canvas laid down over canvas, 60 x 72 inches (left)

Over all, the works share an ineffable aesthetics that Roenisch has managed to grasp. A delightful show.

Hugh Alcock

Images are courtesy of Clint Roenisch Gallery.

*Exhibition information: The Thawing of the Great Bear / Group Show, March 10 – May 15, 2021, Clint Roenisch Gallery, 190 Saint Helens Ave, Toronto. View the exhibition online