Food is not just a means for survival. Food can be a site of intimacy, charged with memory and meaning, a feeling of belonging, and a place to gather. It is quite fitting then that Hangama Amiri’s and Melissa Joseph’s intricate handwork of textiles take on the theme of food in Gathering, currently showing at Cooper Cole. The cultural and domestic precedents of quilting and felting mirrors that of making food. Both are a slow art, a language of touch, the pulling of thread, or the kneading of dough. You might recall your mother mending a rip on your shirt, your grandfather’s secret sauce, or your family get-togethers that last hours after the last bite of dinner was taken. It is a labour of love, an occasion for connection. Amiri and Joseph capture these memories and preserve them into each manually worked stitch and piece of fabric, welcoming you to share with them the tenderness and warmth of food.

Installation view of Hangama Amiri and Melissa Joseph, Gathering at Cooper Cole

Within the exhibition space, the artworks are neatly arranged like dishes around a table with the main dish sitting on a platform in the centre of the room. Made of needle felted wool mounted in a uniappam mold, this so-called main dish is Joseph’s My favourite Appam (and Idli) Wallah. Uniappam, appam, and idli are variations of Indian rice cakes, made by using a mold. Wallah means “one in charge of” and is typically used in combination with a noun. We see an image of a father figure fragmented into the individual compartments of the uniappam mold, the eponymous appam and idli chef. Seemingly a very simple execution of portraiture that ignites your senses of smell and taste. Joseph’s piece is loaded with both cultural and familial memory, a universal and personal sentiment of a close family member making your favourite snack, most likely from a recipe passed down through generations, not written down, but a recipe that lives on in these intimate moments between kin.

Melissa Joseph, My favourite Appam (and Idli) Wallah, 2022, needle felted wool on industrial felt in found uniappam mold, 3 x 10 inches

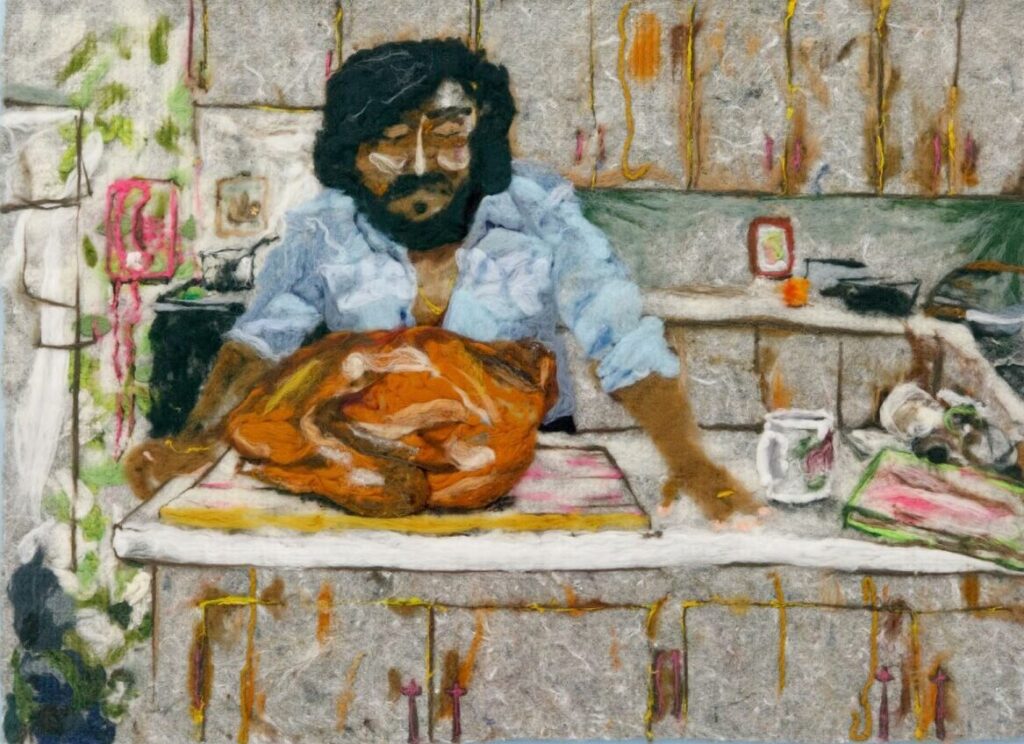

A similar piece from Joseph hangs on the wall. This time, Uncle Bill and his midget whites is felted onto a silver plate. Both the uniappam mold and the silver plate are found objects. They are artifacts that Joseph reanimates by literally embedding them with her memories of family. These tender memories become synonymous with the food that would otherwise sit inside the mold or plate. While Joseph’s work can be imbued with her personal experiences as a second-generation American, referencing specific people in her titles or using cultural materials, she is still able to impart the collective experience of immigrant life, inviting viewers to reflect on what it means to belong.

Melissa Joseph, Thanksgiving 1986, 2025, needle felted wool and recycled sari silk, 31 x 45 inches

On the other hand, Amiri’s painterly textiles approach the theme of food through the still-life genre. Still-life has a longstanding history with its initial rise in the seventeenth century being closely linked to colonial ventures and international trade. These paintings often depicted ‘exotic’ treasures and curiosities. Amiri co-opts the inherently imperialist still-life genre, and instead, uses it to express community, and the intangible culture associated with feasts and gatherings.

Hangama Amiri, The Dinner Table, 2024, denim, cotton, chiffon, linen, muslin, silk, dye canvas, polyester, gauze, velvet, mesh polyester, and Jack Lenor Larson fabrics, 77.5 x 55 inches

It could be argued though that The Dinner Table is not a still-life. The composition is filled with movement, packed with many textures from the various kinds of fabrics Amiri sewed together, and an assortment of dishes and utensils, congregated around a vibrant flower arrangement. Hands reach out from outside the frame to grab themselves a serving of food. We are transported to a room crowded with relatives, overlapping conversations and the smell of freshly cooked dishes fill the air. Still-life with Oysters and Lucky Lime is a similar scene, but instead, we take on the perspective of someone sitting at the table with a plateful. Once again, the still-life becomes animated and vibrant as the viewer gets invited into Amiri’s family meal.

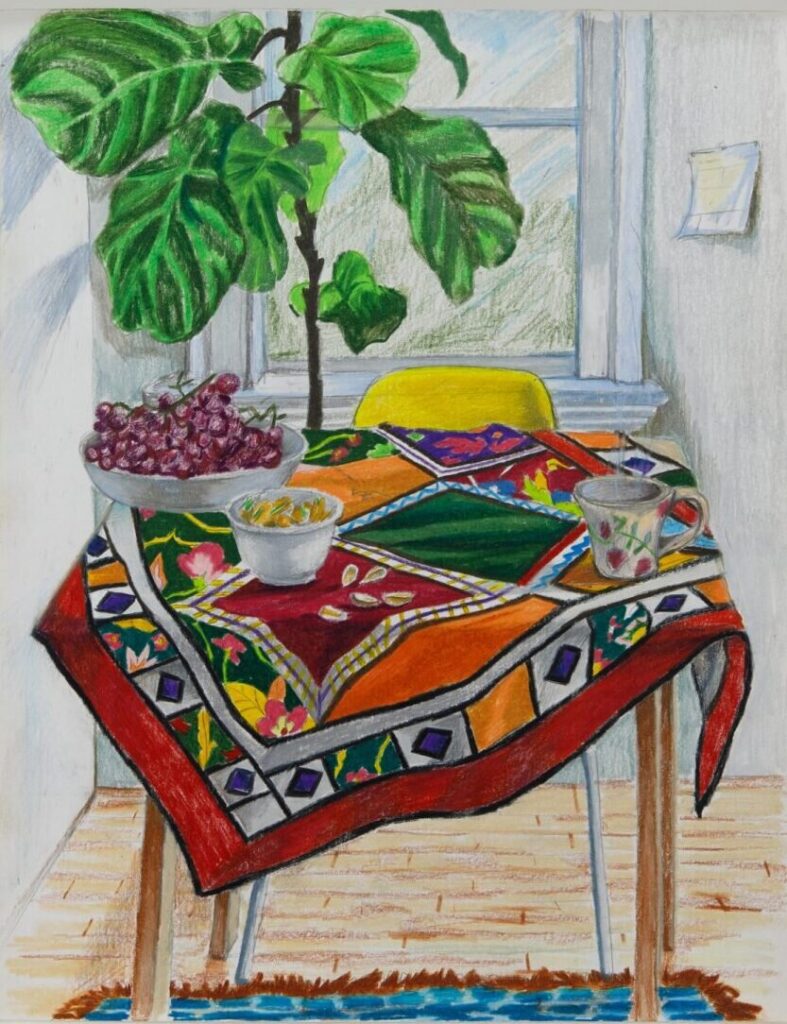

In tandem with Amiri’s grand and lively tapestries are smaller, intimate scenes rendered in coloured pencil on paper. Though still infused with vibrancy seen in the sewn textiles, Still-life with Almonds on Afghan Textiles and Eid, are more quiet vignettes, and void of any figures. However, the food depicted nevertheless contains a human touch; the carefully arranged bowls of grapes and almonds, or the preparing and setting of dishes for Eid. The invisible labour of love can be seen in the everyday objects of our home. The still-life is no longer a means to boast the exploits of colonial travel, but to express appreciation for the things that make our home and community.

Hangama Amiri, Still-life with Almonds on Afghan Textile, 2022, colour pencil on paper, 14 x 11 inches

Using food as both subject and symbol, Amiri’s and Joseph’s artworks wholly evokes the memories of shared meals. Through visual cues, we are reminded of the smell of freshly homemade dishes, the light symphony of spoons scraping plates, the overlapping chatter of your aunts and uncles gossiping, and the taste of your favourite dish that no professional chef can ever replicate. Gathering is a tribute to family and to those who work to put food on the table, to create a home.

Installation view of Hangama Amiri and Melissa Joseph, Gathering at Cooper Cole

Rebekah Barone

Images are courtesy of Cooper Cole Gallery.

*Exhibition information: Hangama Amiri and Melissa Joseph, Gathering, March 21 – April 26, 2025, Cooper Cole Gallery, 1134 + 1136 Dupont Street, Toronto. Gallery hours: Thru – Sat: 12 – 5pm.