Prior to seeing Form Follows Fiction: Art and Artists in Toronto at the University of Toronto Art Museum, I was extremely skeptical. With a scope as large as ‘Art and Artists of Toronto’ and a showcase of work by 86 artists, I wondered how someone could thematically arrange such a broad spectrum of work into a cohesive exhibition. But after seeing it three times, hearing the curator’s talk, and reimagining the diversity of work to be a direct reflection of the diversity of Toronto, my skepticism was put to bed.

The theme of identity and the desire to define a sense of place is universal. I’ve had the privilege of discovering that after a brief period of separation, a weekend in Montreal or a year in London, the cultural and environmental characteristics of a city become much more distinct. Whether you’ve been here your whole life or migrated recently, everyone defines their sense of self through their similarities and differences to others—and the artists in Form Follows Fiction do just this. Using performative and allegorical processes, described as such by curator Luis Jacob, the work explores how the artists’ conditions have shaped their sense of place.

Form Follows Fiction is not historical, chronological, or a history of art in Toronto. Instead, over 100 works are thematically arranged under four outlined gestures: mapping, modelling, performing, and congregating. While the works span a period of about 50 years of artistic production, with historical documents dating as far back as the eighteenth century, Jacob’s exhibition was an honest and exciting exploration of artists in Toronto.

The exhibition was split between Justina M. Barnicke Gallery and the University of Toronto Art Centre. I luckily started at Justina M. Barnicke Gallery, where the works played a major introductory role. Through extremely diverse subject matter and materials, the work loosely dealt with how history informs our cultural environment. Whether asking more complex conceptual questions surrounding the formation of space or directly referencing legislative frameworks, the allegorical subtleties of the works create a powerful narrative about the ‘vacant lot’—a term used by Jacob as a metaphorical tool to consider how space is mapped both literally and figuratively.

The first work that strikes you upon entering the gallery is Premises for Self-Rule by Saulteaux First Nations Canadian artist Robert Houle. The work is comprised of four canvases visualizing four legislative acts in Canadian history. The middle canvas on the far right wall refers to the ‘Indian Act’ of 1876, a legislative act that became the initial basis for aboriginal assimilation by disallowing the practice of aboriginal ceremony, determining the land base of aboriginals in the form of reserves, and defining who qualified as an ‘Indian’ through Indian status. Despite undergoing numerous amendments, the act is still in place today (which is difficult to imagine considering that Canada was the first country in the world to adopt multiculturalism as an official policy in 1971). Houle’s works act as a ‘panorama’ of a legislative framework that contributed to the cultural upheaval of Indigenous people. Mediated between tradition and an imposed assimilation into Canadian culture, many natives still experience the ramifications of these highly controversial acts today.

Robert Houle, Premises For Self-Rule, 1994, oil on canvas, photo emulsion on canvas, vinyl

Robert Houle, Premises For Self-Rule, 1994, oil on canvas, photo emulsion on canvas, vinyl

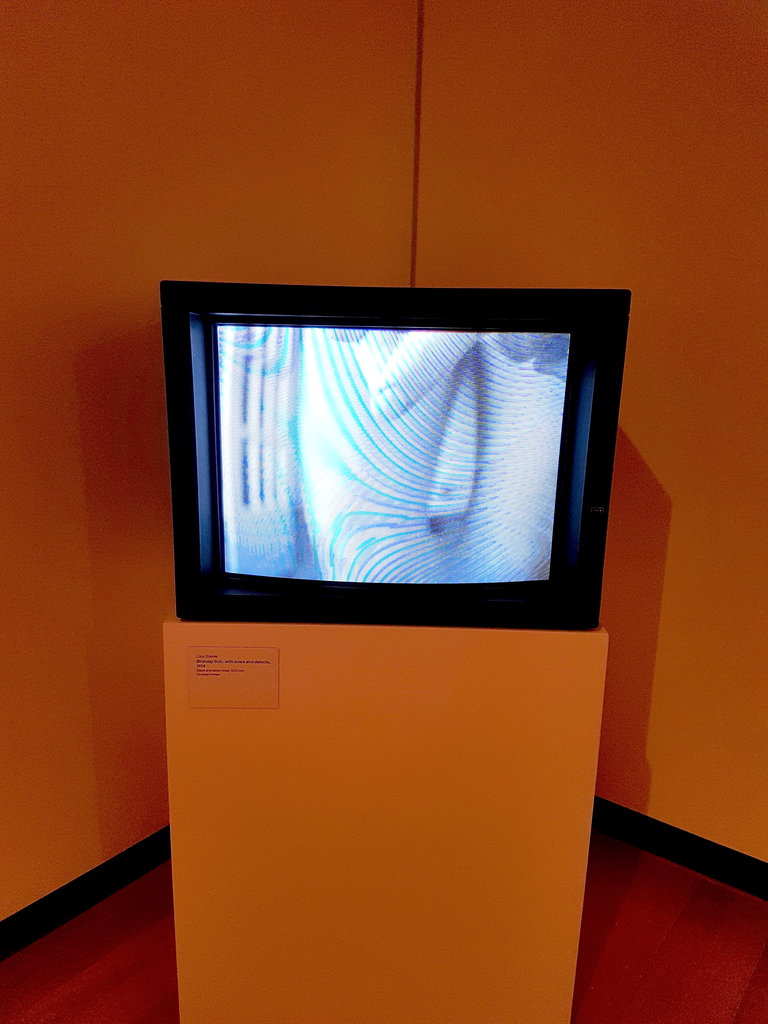

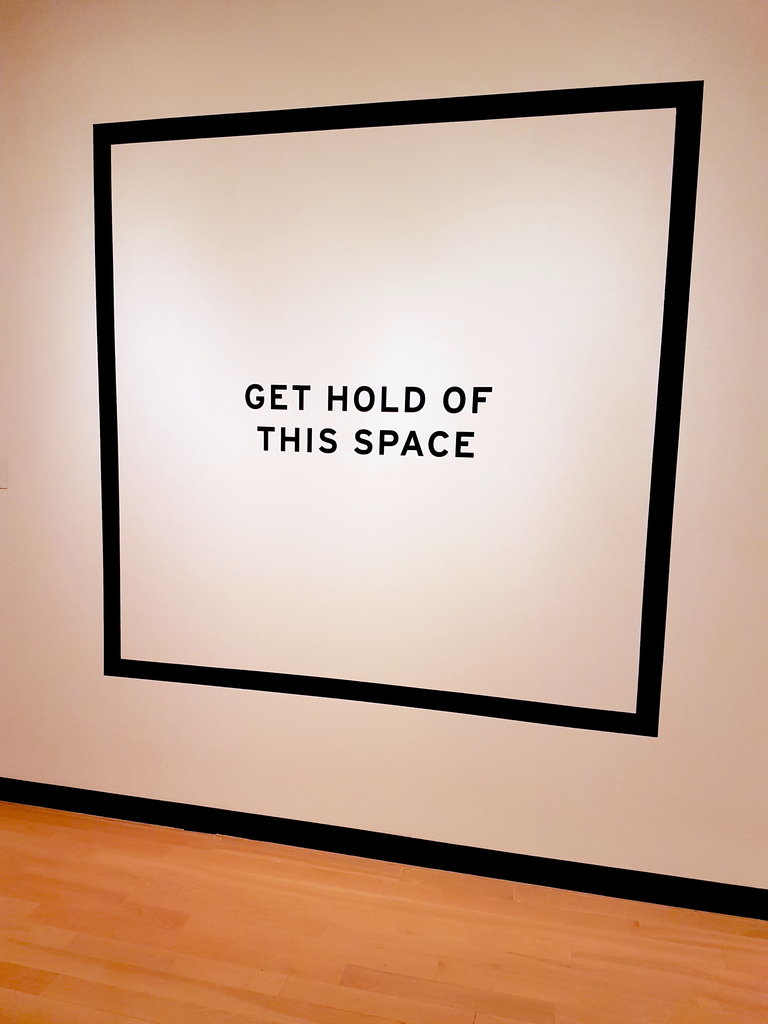

Other notable, and slightly less politically charged, works in this gallery were Lisa Steele’s Birthday Suit—with scars and defects, Gordon Lebredt’s Get Hold of This Space, and Carole Conde & Karl Beveridge’s Work in Progress. Steele, born in Kansas City now living and working in Canada, created this video on the occasion of her 26th birthday, showcasing a history of the artist’s life through various injuries and scars and revealing another method of mapping. Winnipeg-born Gordon Lebredt presents a giant black box outlined on the wall with the words ‘GET HOLD OF THIS SPACE’ nestled inside, which articulates our relationship with space using the metaphorical notion of the ‘vacant lot’.

Lisa Steele, Birthday Suit—with scars and defects, 1974, black and white video, 13:23 min

Lisa Steele, Birthday Suit—with scars and defects, 1974, black and white video, 13:23 min

Gordon Lebredt, Get Hold of This Space, 1974/2010, latex paint and vinyl lettering

Gordon Lebredt, Get Hold of This Space, 1974/2010, latex paint and vinyl lettering

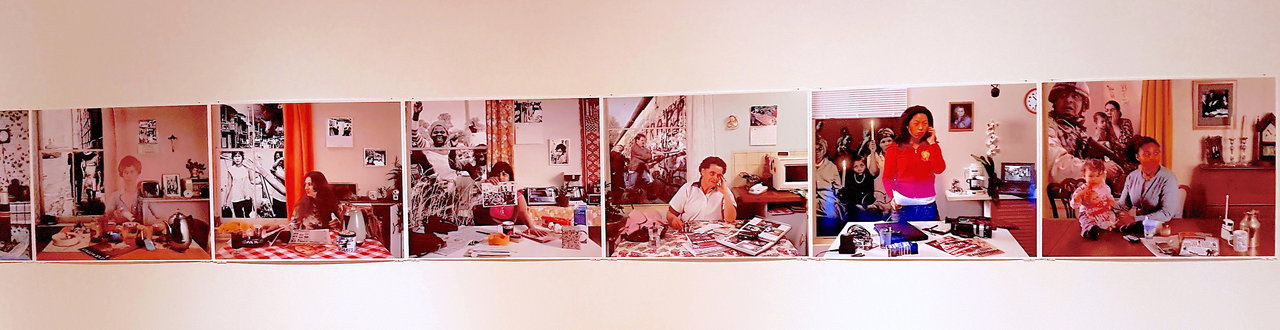

Canadian artists Conde and Beveridge present photographic panoramas that demonstrate a view of working women over twelve decades. Each woman is posed in a kitchen, where objects have been thoughtfully staged and the windows frame a documentary photograph relating to the politics of the period.

Carole Conde & Karl Beveridge, Work In Progress, 1980-2006, archival pigment print

Carole Conde & Karl Beveridge, Work In Progress, 1980-2006, archival pigment print

Thus far, the exhibition was winning me over, but as an important aside, the curator’s talk played a major role in my reception of the work. Without it, I didn’t fully appreciate the relevance of certain works or their subtle relationships to one another. Now, to be clear, I am not calling for text panels about the thematic arrangement (which were also not provided), but individual explanations of specific works. For fear of sounding old fashioned: an exhibition of this scale needed some explanatory text panels. For contemporary art exhibitions outside of a major institutional setting, this practice is generally unheard of, but explanatory texts are not just for museums or posthumous shows.

Before listening to the curators talk, I felt that some of the works were misplaced, but after it I had those “A-ha!” and “Ohh” moments, where I thought, “NOW I get it!” For those unable to attend, explanatory texts could have filled in the gaps and brought the exhibition together. As someone in the arts, there is always that initial fear of embarrassment when you can’t make the leap between artwork and concept, but in many ways this gap is reflective of the exhibition and not a fault in an audiences viewing methodology—especially in a show with over 100 works.

Moving across to UTAC, which is markedly larger, I braced myself for an abundance of work. The first piece that captured my attention was Lifestyle Series by Ojibway artist Keesic Douglas. Four photographs feature an Anishinaabe couple surrounded by stereotypical features of their culture. Each photograph is a scene, staged and lit like a movie set. The couple are surrounded by dream catchers, stereotypical ‘Indian’ statuettes, deer skin drums, a Pocahontas mug, and many other ‘Indigenous’ objects. Living in these tableaus, the couple are surrounded literally, and figuratively, by the Indigenous stereotypes persisting in contemporary Canada. As Douglas once said in an interview: “I see photography as a reflection of the things around us.”

Keesic Douglas, Lifestyles, 2007

Keesic Douglas, Lifestyles, 2007

At this point I realized something: native and migrant groups likely experience a ‘sense of place’ quite differently. Indigenous people have dealt with a (forcible) shift towards assimilation against their established customs and traditions, while many migrants assimilate through choice. The experiences of these two groups created an interesting dialogue between how they are defined in relation to one another and how they mediate the space in-between. This is one of the exhibitions greatest successes, the representation of a diverse spectrum of artists from Indigenous, Canadian and migrant perspectives.

Despite outlining four thematic gestures at the beginning of the exhibition, there is no signage to designate which one was which, and no attempt to simplify the works into categories. This approach allowed the art and artists to escape restrictive definitions under thematic titles, and reiterated the diversity reflective of every major city. One of the greatest disservices an exhibition of this scale can do is to presume that 86 artists can be organized into neat categories.

As you delve deeper into the exhibition you are greeted by two crocheted banners stating “WE CAN’T COMPETE” and “WE WON’T COMPETE”. Created by Canadian artists Deirdre Logue and Allyson Mitchell, founders of FAG (Feminist Art Gallery), the works seek to reject the patriarchal art system, calling the biased structures that continue to govern contemporary artistic practice into question. FAG opens up spaces and creates opportunities for queer, feminist and local communities to converge and overlap. Negating existing structures and proposing a new trajectory, this work dealt with the same metaphoric themes as the work around it.

Deirdre Logue and Allyson Mitchell, CAN’T/WON’T, 2012, crocheted squares

Deirdre Logue and Allyson Mitchell, CAN’T/WON’T, 2012, crocheted squares

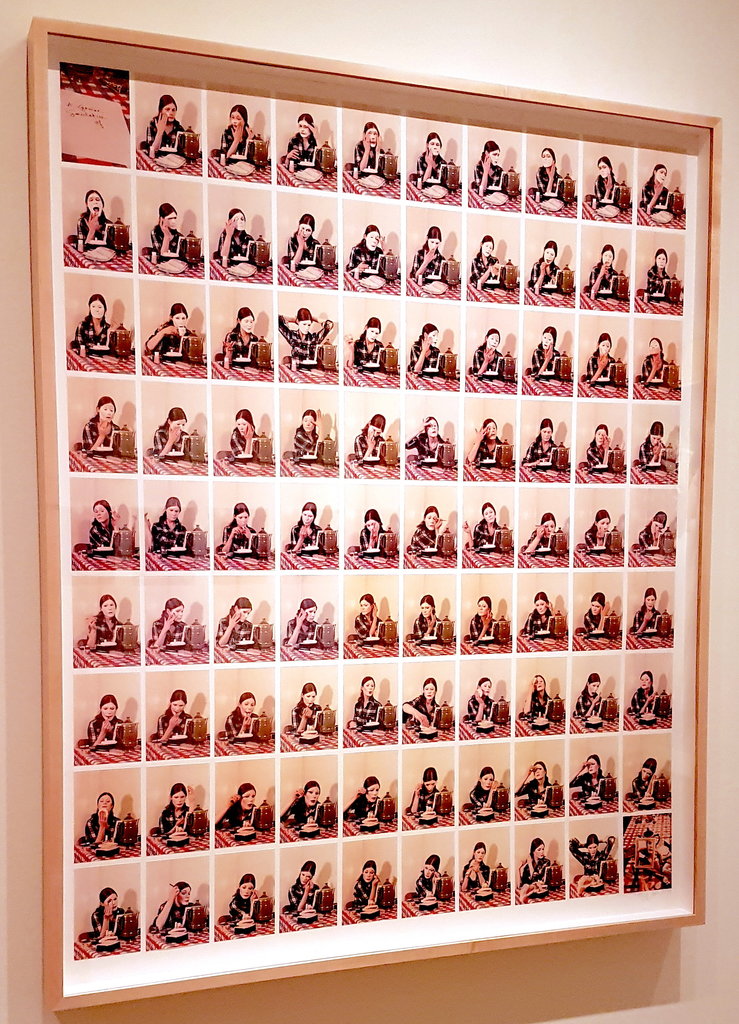

In his talk, Jacob described this area through the allegorical notion of ‘modelling’. In society there exists a series of models—systems used as an example to follow or imitate. In almost every instance, we either reject them, do not measure up to them, or feel that we are much more than them. This whole room, from Suzy Lake’s A Genuine Simulation of… to Nobuo Kubota’s Reflections I, aims to define an individual sense of self. Suzy Lake, an American-born artist living and working in Toronto, created a series of photographs depicting the artist with varying amounts of makeup on her face. She is recognizable in some photographs while in others the makeup sits on her face like a mask. Lake raises key questions about authenticity, and how conforming to societal ‘models’ can turn you into an artificial version of yourself. Kubota’s work, on the other hand, is a matter-of-fact kind of work. The Canadian artist created a unified mirror that looks like two mirrors intersecting one another. This work, in the centre of the space, ties the artworks together. It is an invitation to look at oneself directly.

Suzy Lake, A Genuine Simulation of…, 1973-74, chromogenic prints drymounted

Suzy Lake, A Genuine Simulation of…, 1973-74, chromogenic prints drymounted

Nobuo Kubota, Reflections I, 1969, wood and mirror

Nobuo Kubota, Reflections I, 1969, wood and mirror

Having only spoken about eight works, I could have easily written about every piece in Form Follows Fiction. Other major artists in this exhibition worth noting are Michael Snow, General Idea, Joanne Tod, Joyce Wieland, and many others; all of which are featured in the Art Gallery of Ontario’s Toronto: Tributes and Tributaries, 1971-1989. I initially wanted to review Form Follows Fiction in isolation of the AGO’s showcase, but there were too many comparisons to not give it a passing nod.

Toronto: Tributes and Tributaries, 1971-1989 brings together more than 100 works by 65 artists and collectives. It explores art in Toronto in the 70s and 80s, a time of economic prosperity as well as social and political upheaval. The AGO structured the exhibition as you would expect; the text panels and thematic organization were definitive of an institutional exhibition. The sections dealt broadly with ‘Performance’, ‘Self/Portrait’, ‘The Body’, ‘The Image’, ‘Representation’, etc. Overall, it was a fantastic exhibition. However, its greatest failure was Form Follows Fiction greatest success: it simplified a vast body of work into neat categories.

In Form Follows Fiction, every work deserved the time spent, which perhaps amounted to the exhibitions greatest shortcoming. With too many works to provide explanatory texts, and not enough time to appreciate them all, only a proportion of the show could be absorbed by any one visitor.

Text and photo: Megan Kee

*Exhibition information: Form Follows Fiction: Art and Artists in Toronto, September 6 – December 10, 2016, Justina M. Barnicke Gallery and University of Toronto Art Centre, under its new name: Art Museum University of Toronto, 7 Hart House Circle and 15 King’s College Circle, Toronto. Gallery hours: Tue & Thu – Sat 12 – 5 pm, Wed 12- 8 pm.