Press Preview, Tuesday, October 16, 2012

ART GALLERY OF ONTARIO

The Art Gallery of Ontario welcomed nearly 100 journalists to the media preview of Frida & Diego: Passion, Politics and Painting on October 16, 2012. We were greeted with gingerbread cookies – depicting one of Frida’s famous portraits with flowers – I still saving it as I just can’t bring myself to eat it.

AGO director and CEO Matthew Teitelbaum gave remarks and hosted a discussion with Carlos Phillips Olmedo, director of the Museo Dolores Olmedo, and Dot Tuer, curator of the exhibition.

(From left) AGO director and CEO Matthew Teitelbaum, Carlos Phillips Olmedo, director of the Museo Dolores Olmedo and curator of the exhibition Dot Tuer

(From left) AGO director and CEO Matthew Teitelbaum, Carlos Phillips Olmedo, director of the Museo Dolores Olmedo and curator of the exhibition Dot Tuer

(From left): curator of the exhibition Dot Tuer, AGO director and CEO Matthew Teitelbaum and Ambassador Mauricio Toussaint, Consul General of Mexico in Toronto

(From left): curator of the exhibition Dot Tuer, AGO director and CEO Matthew Teitelbaum and Ambassador Mauricio Toussaint, Consul General of Mexico in Toronto

As Carlos Phillips Olmedo pointed out Rivera was the 3rd most celebrated artist in the 1930’s, after Picasso and Matisse. Following the Great depression and the Russian Revolution, Mexico was the centre of the Spanish speaking world. In his historical murals Rivera idealized the revolutionary masses and the pre-Columbian past. In his works the Mexican revolution became bigger than life. The exhibition of his 7 portable murals travelled the world and he received many comisssions, including one for the Rockefeller Centre.

Visitors in front of Diego Rivera’s mural

Visitors in front of Diego Rivera’s mural

Diego Rivera (1886-1957). Vendedora de alcatraces, 1943 (Calla Lily Vendor, 1943), oil on masonite, 150 x 120 cm. The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of Mexican Art. (C) Banco de Mexico Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museum Trust, M.D.F./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Diego Rivera (1886-1957). Vendedora de alcatraces, 1943 (Calla Lily Vendor, 1943), oil on masonite, 150 x 120 cm. The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of Mexican Art. (C) Banco de Mexico Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museum Trust, M.D.F./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Frida Kahlo found frame again in the 1970s through the feminist movement. Frida, however wasn’t oppressed at any point of her life. Quite the opposite. She grew up in a middle class family. Her father was a photographer from German origins. It was through him that Kahlo gained knowledge of the magics and the powers of photography, as well as meeting a large group of intellectual friends she later shared with Rivera. What connected them was their idealism, their revolutionary political positions and their love for the contry. Rivera was an accomplished artist, 20 years Kahlo’s senior when they married.

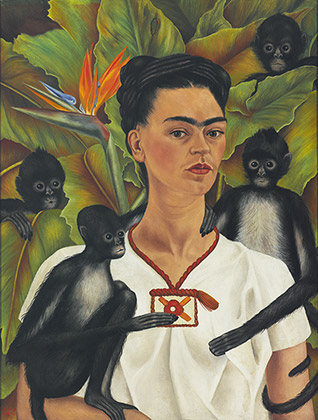

Kahlo’s most famous works are her self-portraits. Of the 143 paintings she completed, 55 are self-portraits. She often used indigenous Mexican symbolism, like idols and animals that represent the underworld and also as her surrogate children. In her paintings, physical pain and psychological wounds are central elements.

Frida Kahlo (1907-1954). Autorretrato con monos, 1943 (Self-Portrait with Monkeys, 1943), oil on canvas, 81.5 x 63 cm. The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of Mexican Art. (C) Banco de Mexico Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museum Trust, M.D.F./Artists Rights Society (ARS), NewYork

Frida Kahlo (1907-1954). Autorretrato con monos, 1943 (Self-Portrait with Monkeys, 1943), oil on canvas, 81.5 x 63 cm. The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of Mexican Art. (C) Banco de Mexico Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museum Trust, M.D.F./Artists Rights Society (ARS), NewYork

Rivera was a charismatic person and a talented storyteller – the centre of every party. Kahlo was a more private person. She couldn’t move around a lot because of the physical pain she suffered after a debilitating bus accident at the age of 18. Her paintings embody the spiritual anguish caused by Rivera’s infidelity and by her inability to have children.

Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) Hospital Henry Ford, 1932 (Henry Ford Hospital, 1932) oil on metal, 31 X 38.5 cm Collection Museo Dolores Olmedo, Xochimilco, Mexico (C) Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) Hospital Henry Ford, 1932 (Henry Ford Hospital, 1932) oil on metal, 31 X 38.5 cm Collection Museo Dolores Olmedo, Xochimilco, Mexico (C) Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

This is the first time when Rivera’s and Kahlo’s works are exhibited in the same room. It brings out the intimacy of Rivera’s smaller paintings and drawings and shows the monumentality underlining some of Frida’s work. I’ve never seen Kahlo’s latest, miniature paintings before, and their almost abstract beauty surprised me.

There are some nice quotations projected on the gallery’s wall showing their admiration for each other’s “vision of the truth”. A short film made by Nickolas Muray also depicts their passion for each other. Photographs by Lola Alvarez Bravo, Bernard Silberstein and others help tell the story of one of the most prolific and politically charged couples of the 20th century.

The Frida and Diego catrinas are a nod to the practice of portraying loved ones as skeletons during the Day of the Dead festival on November 1 and 2, a tradition popularized by the Mexican graphic artist José Guadalupe Posada (1851-1913). The AGO invited Shadowland to create the Judas and Posada figures you see in this gallery. These five figures were made by Shadowland artists Anne Barber, Brad Harley, Angela Thomas, Kristi White and Barbara Klunder.

Text: Emese Krunák-Hajagos. Photo: Mauricio Contreras-Paredes