For this year’s Sotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival, curator Timothy Prus pulled together an exhibition at MOCCA with an impressive count of 198 photographs. Titled Collected Shadows, the show is culled from the Archive of Modern Conflict’s collection of over four million images spanning from the mid-nineteenth century to the present. The Archive of Modern Conflict (AMC) is a Canada- and UK-based organization, whose practice of collecting focuses on diversity rather than renown; it amasses works from all across the globe by both amateur photographers and well-known names, such as photography giants Robert Frank and Étienne-Jules Marey.

Installation view. Photo: Alice Tallman

Installation view. Photo: Alice Tallman

Distilling a digestible exhibition from such an extensive archive is a daunting task, but Prus bravely approaches the dizzying diversity by working with it rather than against it. The 198 photos hang on rich, aubergine walls, divided into clusters of as few as four and as many as over two dozen. Avoiding any obvious chronological organization, each grouping is a mix-and-match of images from various periods, sometimes loosely linked by technique or style, other times by theme. The photos in each cluster are arranged in a free-form salon style, spurring the eye to dart playfully and spontaneously from one picture to another.

Bertha Jaques (American), Plant Study, Cyanotype, c. 1910 (left) and Dorothy Wilding (British), Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, Silver Gelatin Print, c. 1954 (right)

Bertha Jaques (American), Plant Study, Cyanotype, c. 1910 (left) and Dorothy Wilding (British), Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, Silver Gelatin Print, c. 1954 (right)

The exhibition places each archival photograph in a fresh context, side-by-side with images from other times and other places. The meaning of an image is never stable, its signification always dependent on its context. This show stages a wealth of chance meetings between pictures of remote subjects, reanimating the images and making them signify in unexpected ways. In one grouping, Bertha Jacques’ plant study cyanotypes (c.1910) appear next to society photographer Dorothy Wielding’s picture of Queen Elizabeth (1954). In another cluster of photos, a texturally captivating shot of lentils by Aleksandr Khlebnikov (c.1930) is shown near a somber picture of fellow Russian Kasimir Malevich’s last moments (1935).Each of these imaginatively grouped clusters of photos is a fountainhead of associations and clashes – between the mundane and the extraordinary, between nature and technology, and among divergent times, places, and peoples.

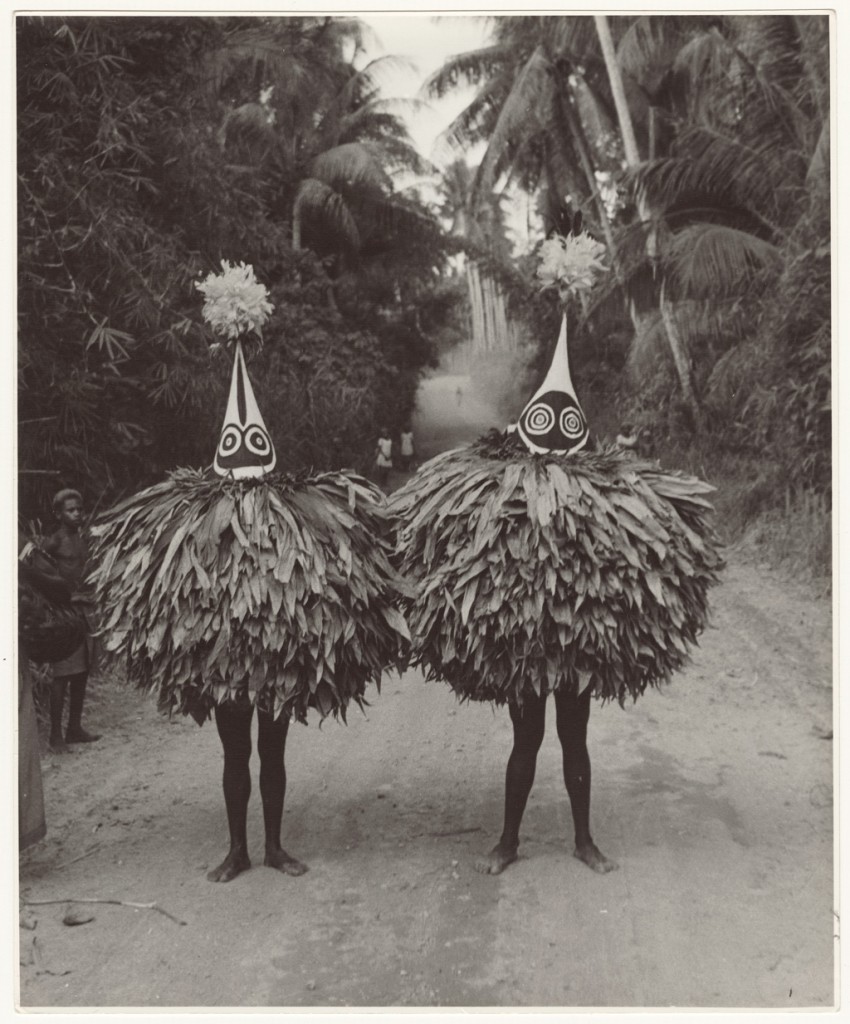

Maxwell R. Hayes (Australian), Duk-Duk members, Silver gelatin print, 1964

Maxwell R. Hayes (Australian), Duk-Duk members, Silver gelatin print, 1964

The AMC declares as its task to engage with and constantly reassess the legacy of the incoming photographic stream – but it does just as well engaging with and reassessing the nature of photography itself. A photographic image is partly the result of a mechanical process that makes an indexical recording the world beyond the viewfinder. But the photograph is also an interpretation of reality by the photographer, who chooses, frames and manipulates that outside world. The indexical quality of photography makes it an appealing medium for objective record-making for diverse purposes, from judicial to scientific. Paul-Émile Miot’s Mi’Kmaq woman, Newfoundland (c. 1859) places emphasis on the factuality of the photographed subject, conceiving the photograph as objective material for ethnographic knowledge.

Paul-Émile Miot, Mi’Kmaq woman, Newfoundland c. 1859

Paul-Émile Miot, Mi’Kmaq woman, Newfoundland c. 1859

But hanging nearby is Frank Coster’s Spirit photograph(1890), in which three ghostly busts hover over a seated portrait of a woman. This manipulated photograph deviates from factual recording, moving toward an image-making that makes the agency of the photographer more visible. As a reflection on the nature of the photographic medium, this exhibition makes evident the tension between objective recording and subjective interpretation that characterizes photography, which never escapes its indexical essence but which is also boundless in creative possibilities.

Frank Coster (American), Spirit photograph, Cyanotype, c. 1890

Frank Coster (American), Spirit photograph, Cyanotype, c. 1890

The immersive environment of this exhibition produces a hyperawareness of time and its relentless drive forward. Susan Sontag called the photograph a memento mori, a reminder of the mortality and mutability of the depicted subject. The photograph foregrounds the captured moment as something that has passed and no longer is; but it is paradoxically also a slice in time preserved, each viewing bringing the past back from the dead into a confrontation with the present. This is evident in a picture of two Nepalese women taken in 1890 by an unknown photographer. Though the image documents a historical moment that has long passed, the gaze of the two women stare out at the viewer and creates a connection that sustains the subjects’ presence in moment of encounter with the image. This provocative tension between presence and absence pervades the viewing of many of the photographs in this exhibition, lending the experience an eerie but poignant uncanniness.

Commissariat à l’énergie atomique DAM (French), Atomic trial on Mururoa atoll, Tahiti, Colour print, 1970

Commissariat à l’énergie atomique DAM (French), Atomic trial on Mururoa atoll, Tahiti, Colour print, 1970

The show comes to a vivid close with a bang, culminating in a group of photographs linked by the themes of fire, burning, eruptions, and explosions. Taking in the last of the pictures, no neatly packaged grand narratives come to mind. What surfaces instead are myriad stories of diverse peoples and the worlds they live in and create around themselves. And whether the exhibition’s self-reflexive look at the multi-faceted nature of photography has complicated or clarified our understanding of the medium, we’ll likely start looking at photographs a little differently after. Collected Shadows makes for a mind-jogging primer to the CONTACT festival, before one gets cracking on the other one hundred plus photography shows.

Amy Luo