I Hate Poetry but I Love TV

(or, K.D. @ 4–oh/4–reel)

The callow seeming title of this, Kim Dorland’s eighth solo exhibition with Angell Gallery, is a bluff. In his Toronto studio in August, Kim told me that he likes both poetry and TV. Its false braggadocio rings with second-wave nostalgia for the receding prior nostalgia of an early incarnation of the artist who habitually slipped into the indications of a former adolescent cockiness. Today he nestles the intimate, ephemeral now-ness of time as he watches his children and family (and self) live through instances that occur and vanish in a flicker.

Kim Dorland in his studio. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

Kim Dorland in his studio. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

Yet, while the title is not literally true, it is otherwise apropos. Dorland chooses not to paint with poetic embroidery or temerity. His imagery is prosaically undisguised; his vocabulary reflexively automatic, journalistic, matter-of-fact; his palette ALLCAPS attention-grabbing, vivid, even lurid; and his mark making emphatic with punctuation as much as description. That punctuation inflects…no, directs the amassments of colour on his canvases and it crucially articulates the stories that emerge from his pictures. Dorland’s claimed affinity to television speaks to the day-by-day mesmerisation of far and near exotica (and the commonplace) denatured and re-naturalized by the keyed-up glow of the household screen.

Kim Dorland, Niagara Falls, 2014, 48″ x 60″, oil and acrylic on linen over wood panel. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

Kim Dorland, Niagara Falls, 2014, 48″ x 60″, oil and acrylic on linen over wood panel. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

Home plays a bit role in these latest paintings, all from 2014, insofar as it is only one of many settings for family life, its events, activities and passages. Because, it seems, the artist’s observations of his family might occur anywhere or anytime. His profoundly immersive, psychic recognition of the simultaneous presence, difference and absence of those closest to heart powerfully relocates and envelopes the benchmark portraits of his self-possession (versus their self-possession) in an array of locations. So, even when he is away from home, it feels local and proximate to a specific moment. An image snatched during an evening run, High Park, connotes what Dorland acknowledges as “a melancholic year [as an artist] that doesn’t reflect [his] point of view with respect to his family or his responsibilities”—a not uncommon refrain from a forty-year-old man.

Kim Dorland, Vernissage, 2014, 48″ x 60″, oil and acrylic on linen over wood panel. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

Kim Dorland, Vernissage, 2014, 48″ x 60″, oil and acrylic on linen over wood panel. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

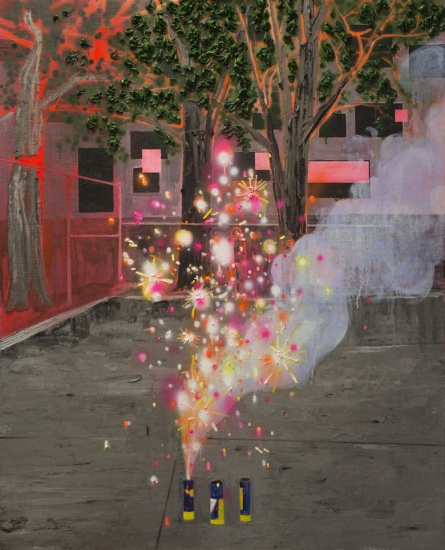

Digital photography is an essential tool and reference for Dorland’s ongoing image archive of daily life passing into the subjects for his paintings. It naturally fits such a prolific and prodigiously gifted artist. Pictorial prowess and facility such as Dorland’s allows for the gradual, uncontrived seeping of meaning into one’s work. For all its outrageous stylizations and exaggerations of colour and form, Dorland’s paintings remain essentially objective. Therefore he does not prefigure or predestine his attitude to their content. By constant return to themes and real views, not only does he gauge the changes of his subjects, but also notices his variances in perceptive and emotional state. Sometimes key incidents shimmer in through placid and routine surroundings, such as a hazy and distant police car parked in the centre of the aforementioned High Park. Similarly, the efflorescent sparkle and fuming of Fireworks almost completely occlude a pair of humble witnesses meekly standing against the back fence of the concrete yard, Dorland’s sons, Seymour, eight, and Thomson, five.

Kim Dorland, Dead End, 2014, 30″ x 40″, oil and acrylic on linen over wood panel. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

Kim Dorland, Dead End, 2014, 30″ x 40″, oil and acrylic on linen over wood panel. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

Kim Dorland, Fireworks, 2014, 60″ x 48″, oil and acrylic on linen over wood panel. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

Kim Dorland, Fireworks, 2014, 60″ x 48″, oil and acrylic on linen over wood panel. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

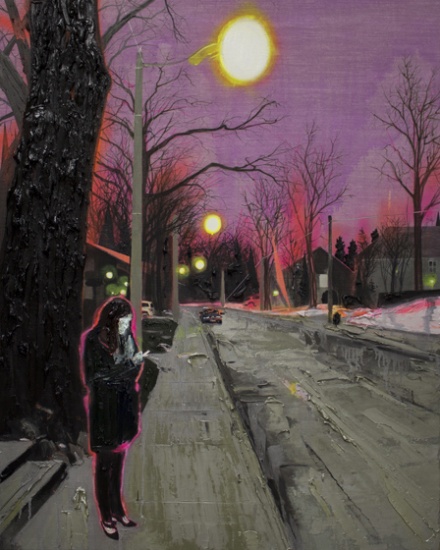

The compositional reference to cell phone images gains consonant ordinariness in that such devices are ubiquitous, possessed by his subjects too. His wife, Lori, is plausibly aglow as she looks to her screen in the winter evening of After the Party. Crystalline flares and a voltaic underpainting refer to how Dorland recorded the scene. In Bleeding Heart, the small screen isolates and rebalances the image, deepening and thickening a garden around Seymour into jungle, where he sits oblivious to its ominous foliage, inspecting a blossom gently with his fingertips, not absorbed in a video game as it might initially appear.

Kim Dorland, After the Party, 2014, 60″ x 48″, oil and acrylic on linen over wood panel. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

Kim Dorland, After the Party, 2014, 60″ x 48″, oil and acrylic on linen over wood panel. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

Kim Dorland, Bleeding Heart, 2014, 48″ x 36″, oil and acrylic on linen over wood panel. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

Kim Dorland, Bleeding Heart, 2014, 48″ x 36″, oil and acrylic on linen over wood panel. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

March Break and Don’t Give Up are two of Dorland’s most effectively pared-down paintings, each with an abstracted, horizontal banding that yields classic, stacked, rectangular order. The elegant simplicity of each is a feat of artistic restraint, nerve and hard-won experience. In March Break, Seymour stretches upward in preparation for a dive into a pool, with concentration, determination, perhaps some trepidation. His taut body and arms are mimicked above by the upright trunks and limbs of bare trees, and contrasted by an unbelievably limber and confident graffiti tag on the grey wall behind. His face, as is standard for Dorland’s figurative treatments, is a slathered impasto of relief-map planes in oil paint which still conveys a specific portraiture. This technique conveys the vertical musculature of his son’s body and also the horizontal surface plane and concealed depth of the water, of which the human body is largely composed. Don’t Give Up, by contrast, is utterly unpopulated. It depicts the fenced-in tennis courts found in Toronto’s Trinity Bellwoods Park. The chain-link has been meticulously stenciled and sprayed, an extruded screen through which appear side-by-side court lines, posts and nets, at once substance and mirage. The foreground is a clover-pocked lawn. Above the fence line, an orange sky churns with latent energy. A bedraggled message, woven into the fence links with ribbon, is the tattered remnant of youthful spontaneity, long since departed. Each painting renders depth ambiguously, treated in distinct zones of colour and technique that are monolithic and gradated at the same time, conjuring the mists or mystery of the imminent future.

Kim Dorland, March Break, 2014, 60″ x 48″, oil and acrylic on linen over wood panel. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

Kim Dorland, March Break, 2014, 60″ x 48″, oil and acrylic on linen over wood panel. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

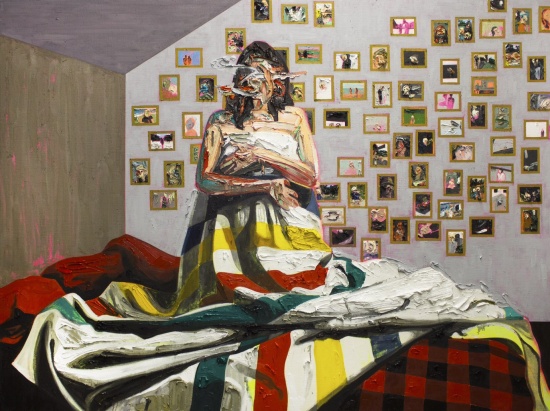

The crowning painting of a glorious show is a portrait of his muse and most frequent subject, Lori. She poses in Bay Blanket #3, as so often, in the nude, however wrapped in a recognizable wool blanket of the Hudson’s Bay Company that she clasps to her breasts and resplendently spreads down her kneeling figure and across the top of the couple’s bed. The painterly treatment of the blanket makes a transition from the thickly-painted flesh and defacement into impasto folds of heavy cloth, especially so around Lori’s torso and gently easing out to reveal some of the textile weave of the canvas on which the paint is brushed, with the signature green/red/yellow/black stripes running up and down or forward and back according to the blanket’s crumpled tumble. The bed is strewn with other rustic red/black patterns of quilting and tossed red pillows beneath her. On the wall behind Lori is a galaxy of framed family photographs, hung with a celebratory disregard for regulated order. Dorland renders each of these photos, so similar to, perhaps identical with, the sources for so many of his paintings, with tender attention to its individual distinction, its specific reference and instance in the artist’s life. He can’t help himself. He strives to keep up with evanescent life by constantly resetting and starting over.

Kim Dorland, Bay Blanket #3, 2014, 72″ x 96″, oil and acrylic on linen over wood panel. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

Kim Dorland, Bay Blanket #3, 2014, 72″ x 96″, oil and acrylic on linen over wood panel. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

Ben Portis

September, 2014

Note: Ben Portis above essay is a curatorial response to Dorland’s recent work produced in conjunction with his exhibition, originally written in September, 2014 and published on Angell Gallery’s website. We thank Ben Portis an Angell Gallery for their courtesy of letting us to publish it.

*Exhibition information: October 4 – November 8, 2014, Angell Gallery, 12 Ossington Avenue, Toronto. Gallery hours: Wed – Sat, 12 – 5 p.m.