Henryck Ross began as a professional photographer for the Polish Press, capturing the world around him as it gradually devolved into the chaos of war. The year was 1940; the Second World War had just begun as the Soviet Union and the Germans annexed Poland within weeks, forcing the French and the British to respond militarily. The war ensued with its massive casualties and unparalleled destruction on both sides, overshadowing the absolute horror that was the persecution, degradation, and systematic elimination of European Jews at the hands of the Nazis. Among all of the Germans’ occupied territories, Poland – with the highest Jewish population of approximately 3,000,000 – faced the worst. A myriad of tactics were employed to handle the “Jewish Question,” ranging from forced emigration to outright execution. One of the solutions was to concentrate the target population, particularly in large urban centers, within a contained section of the city thereby dubbed a “ghetto.” Lodz alone had over 160,000 inhabitants from across Europe, all forced to live in horrifying conditions.

Henryck Ross, Henryck Ross photographing for identification cards, Jewish Administration, Department of Statistics, Lodz ghetto, 1940, Art Gallery of Ontario, Gift from Archive of Modern Conflict, 2007. © 2014 Art Gallery of Ontario

Henryck Ross, Henryck Ross photographing for identification cards, Jewish Administration, Department of Statistics, Lodz ghetto, 1940, Art Gallery of Ontario, Gift from Archive of Modern Conflict, 2007. © 2014 Art Gallery of Ontario

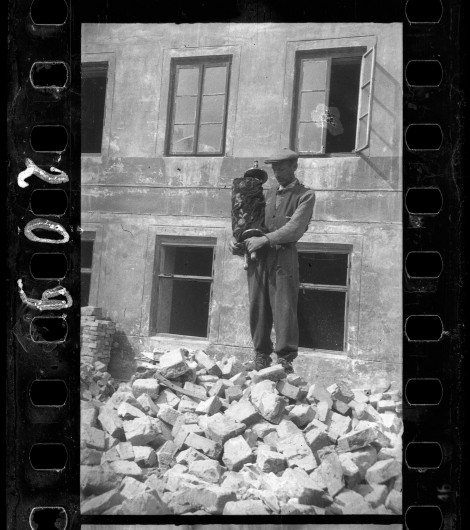

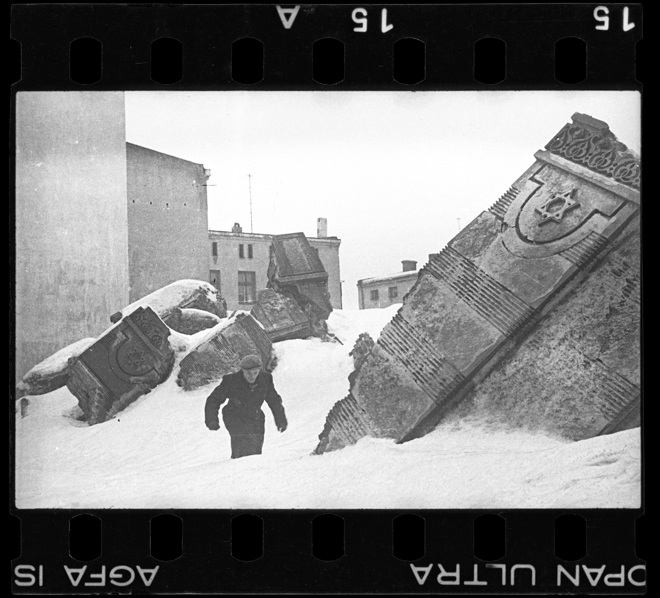

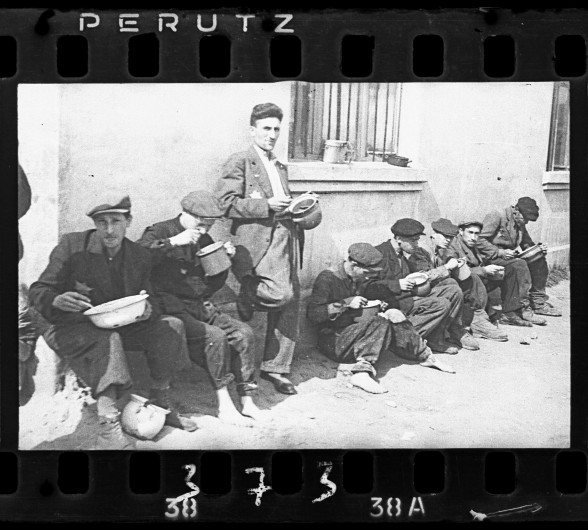

Ross was relocated to the ghetto and, because of his expertise, he was quickly enlisted by the Statistics Department of the Judenrӓte – a council of Jewish elders established to preserve order yet was nothing more than a puppet government for the Nazis. Ross’ job was to firstly photograph the Jewish inhabitants for identification papers, and secondly document administrations, factories, and citizens as propaganda for the regime. His work was heavily restricted to only certain subject matter and anything that deviated from his overseers’ orders was grounds for execution. Therefore, many of his photographs in the exhibition consist of happy citizens in soup kitchens or diligent laborers in textile and leather workshops. Despite the threat of death however, he was keen on telling the true story of the Lodz ghetto, not the false portrayal that satisfied quotas or consciences. Taking every measure to conserve on the department-provided film, he then wandered the confined neighbourhood to capture the sights of his everyday life: streets lined with the cold and homeless, destroyed synagogues (most notably the one on Wolborska Street whose Torah had survived the pillaging), fecal workers who very often suffered from severe illness, and denizens digging holes scrounging for food. Ross constantly risked his life and had doubts that he would even survive through the ordeal, so as a contingency he collected his prints – both from his own work and from his work for the Judenrӓte – and buried them at 12 Jagielnoska Street in the hopes that they would be rediscovered by their liberators. After the liberation Ross recognized that only half of his 6,000 negatives survived.

Henryk Ross, Lodz ghetto: Man who saved the Torah from the rubble of the synagogue on Wolborska street (destroyed by Germans 1939), 1940, Art Gallery of Ontario, Gift from Archive of Modern Conflict, 2007. © 2014 Art Gallery of Ontario

Henryk Ross, Lodz ghetto: Man who saved the Torah from the rubble of the synagogue on Wolborska street (destroyed by Germans 1939), 1940, Art Gallery of Ontario, Gift from Archive of Modern Conflict, 2007. © 2014 Art Gallery of Ontario

Henryk Ross, Lodz ghetto: The ruins of the synagogue on Wolborska street, demolished by the Germans, 1940, Art Gallery of Ontario, Gift from Archive of Modern Conflict, 2007. © 2014 Art Gallery of Ontario

Henryk Ross, Lodz ghetto: The ruins of the synagogue on Wolborska street, demolished by the Germans, 1940, Art Gallery of Ontario, Gift from Archive of Modern Conflict, 2007. © 2014 Art Gallery of Ontario

The range of work that Ross provides is truly telling of those times. On the one hand, it shows the Nazis’ efforts in addressing their racial prejudices as well as the idea they strived for, which took the form of an industrial powerhouse that maximized efficiency and minimized cost. Their propaganda was a means of demonstrating to the German people, the government, and themselves that theirs was a noble and progressive goal. On the other hand, you have the gruesome reality that their efforts manifested that completely juxtaposes their ideal solution. Having both perspectives simultaneously is truly an immersive experience as Ross seems to tell vivid narrative of his, and many others’, experiences. What was most moving, I find, was the assortment of individualised portraits and candid moments of several of the Jewish inhabitants taken shortly after their relocation. There were scenes of smiling and playing children, women enjoying their gardens, and men in suits in professional poses. It seemed like a brief instance of calm separate from the painful life around them – an enduring moment of dignity and joy, even though for many it would sadly be one of their last.

Henryck Ross, Lodz ghetto resident – young child, 1941 – 42, Art Gallery of Ontario, Gift from Archive of Modern Conflict, 2007. © 2014 Art Gallery of Ontario

Henryck Ross, Lodz ghetto resident – young child, 1941 – 42, Art Gallery of Ontario, Gift from Archive of Modern Conflict, 2007. © 2014 Art Gallery of Ontario

Henryk Ross, Lodz ghetto: “Soup for lunch” (Group of men alongside building eating from pails), 1940-44, Art Gallery of Ontario Gift from Archive of Modern Conflict, 2007 © 2014 Art Gallery of Ontario

Henryk Ross, Lodz ghetto: “Soup for lunch” (Group of men alongside building eating from pails), 1940-44, Art Gallery of Ontario Gift from Archive of Modern Conflict, 2007 © 2014 Art Gallery of Ontario

Simon Termine

*Exhibition information: Memory Unearthed: The Lodz Ghetto Photographs of Henryck Ross, January 31 – June 14, 2015, Art Gallery of Ontario, 317 Dundas Street West, Toronto. Gallery hours: Tue – Sun, 10 –5:30, Wed, 10 – 8:30 p.m.