Overcoming History’s Limitations: Lorenza Böttner’s, Requiem for the Norm

Lorenza Böttner’s work rejects conformity to normality by using her own body as the main subject of her artwork. She uses it as a performative space. Her skin is a canvas on which to paint, her frame is a space on which to drape costume, and her form is a mode of movement which expresses meaning.

I had the opportunity to be a Gallery Attendant for the opening night of this exhibit of drawings and photographs, which resulted in me having a lot of time to peruse the work. While making one’s way through the gallery, one notices that the works are laid out in a linear path through time, showing the progression of the artist’s life and artistic career. While I was there, it became evident that Böttner was happy in her body and her joy was communicated through the works to the viewer, with happiness evident in portraits of Böttner where the shutter closed just before a laugh, her eyes crinkling with joy.

Lorenza Böttner and Johanes Koch, Untitled, 1983, black and white photograph

Lorenza Böttner knew hardship well. She was born as Ernst Lorenz Böttner in Chile in 1959. He lost both arms up to the shoulders at eight years of age after falling from an electricity pylon while trying to reach a bird’s nest, which caused a severe electric shock. Ernst Lorenz adapted to his new body, using his mouth and feet to retain autonomy. In art school, Ernst Lorenz began identifying as female and assumed the name Lorenza.

Lorenza Böttner, Untitled, n.d. 35.5 x 27.9 cm

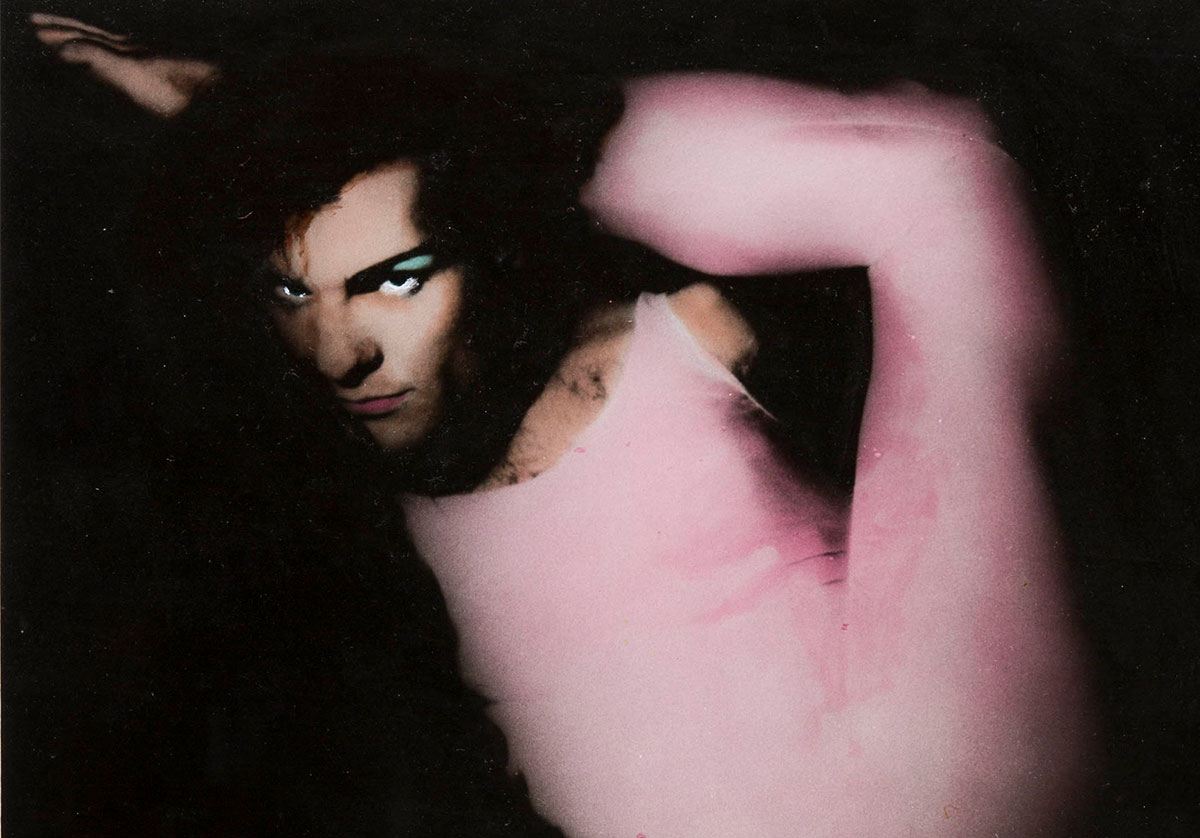

Face Art, 1983, is a series of close-up, black and white portraits of Böttner. Each photo shows a different version of Böttner creating a diverse range of constructed identities by applying pigment to her face. Some of the portraits show heavy pigmentation, with make-up creating darkness around the eyes in the form of masquerade masks, but in other instances embracing a more natural look and incorporates her beard and eyebrows. The variation of the photos, according to the curator Paul B. Preciado, makes the face “an operator of relentless metamorphosis.” The photos are diverse and Böttner turns her head in different directions for each photo. The looks for the self-portraits were made by holding delicate make-up brushes and pencils with her feet and her mouth, using care and steady precision to paint her face. The portraits are close-up shots against a white background that resemble mug shots. Lorenza’s technique used self-portrait as a resistance against, according to Preciado, colonial, medical and police identification photography that assigns assumed identities to people.

Lorenza Böttner, Face Art, Kassel 1983. digital C-print 40 x 29.8 cm

Installation view with Lorenza Böttner, Face Art, 1983, black and white photographs

Dispersed through the gallery are other black and white photographs with Böttner as the subject, wearing different garments. In Untitled, n.d., the artist is the only figure in a plain room with a single chair. One leg is propped up on the chair with her head facing away and twisting towards the viewer, making eye contact. She is wearing a masquerade mask shaped like a sparrow flying downwards towards her nose, alongside sparkling earrings. She wears a tinsel boa around her shoulders which continues to wrap around her upper-torso and a skirt, of the same material, going down to her knees. Kitten heels adorn her feet. Her dark, painted lips are shaped upward and are separated in a wide and genuine smile. Her happiness is evident in this photograph, and this same energy appears many times throughout the exhibit. Böttner creates an identity in the clothes she chooses to put on her body and, in this instance, she looks more feminine. In this photo, Böttner occupies what the curator, Paul B. Preciado, terms a “plurality of positions” as she was interested in the “simultaneity of embodiments rather than identity being a ‘static’ place”. In the variety of works, Böttner’s skin switches between being heavily painted or being natural. In some cases, she chooses to be nude and in other cases cloaks her body with a variety of styles, switching between time periods and traditionally masculine and feminine garments.

Lorenza Böttner, Untitled, n.d., black and white photograph

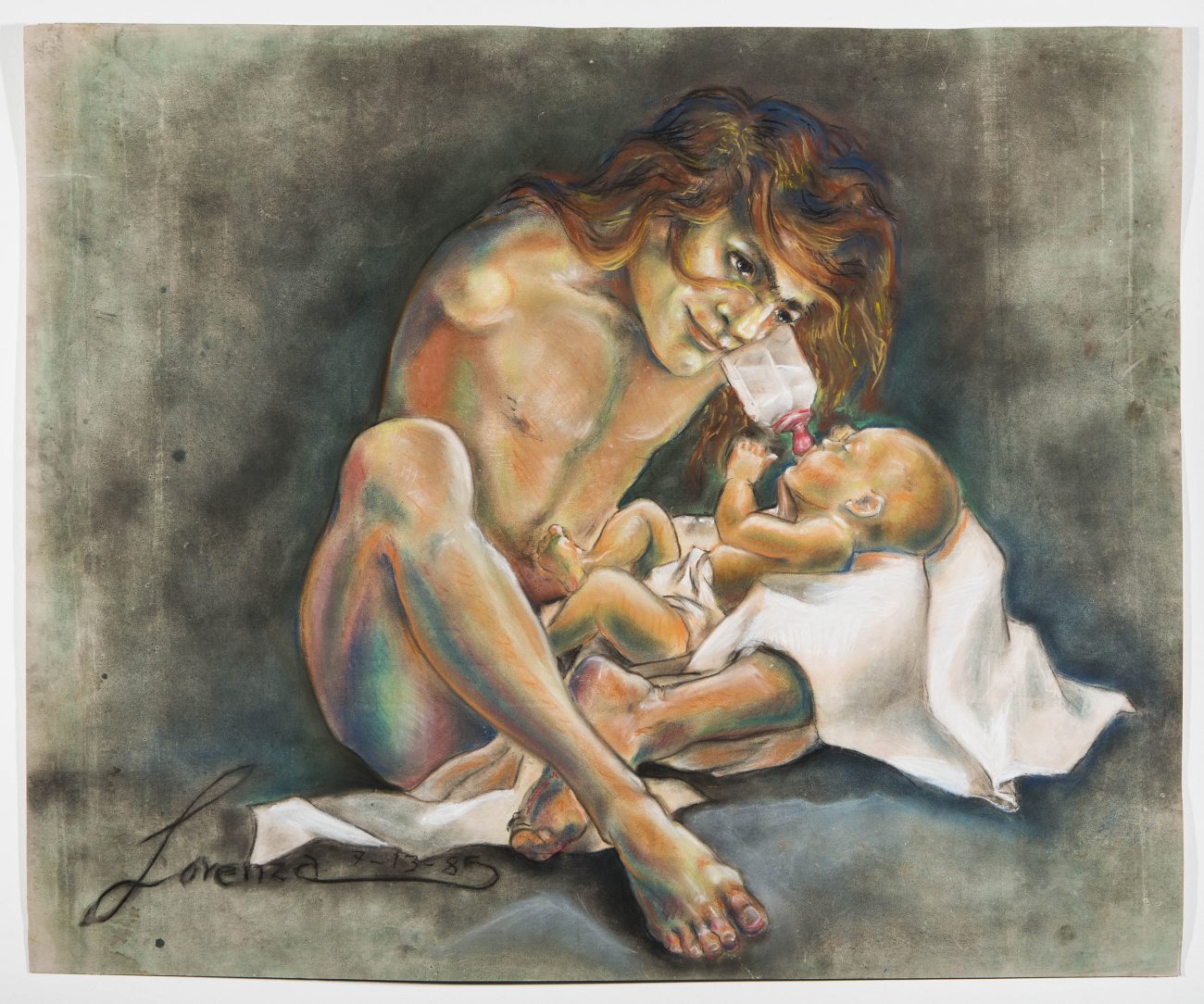

Böttner’s identity seeks another form in, Untitled, 1980. In this pastel drawing she depicted herself nude and seated on the ground, supporting a swaddled infant in the crook of her crossed left leg with her right leg propped up to counter-balance the weight of the child. She balances a bottle of milk in the crook of her neck as the child suckles on it. Böttner’s hair is pushed to one side, flowing down in waves to her shoulders. The figures are brightly colored, contrasting against a non-descript and dark background.

Lorenza Böttner, Untitled, 1980, pastel on paper.

In Untitled, 1985, Böttner has drawn, in pastels, her body in the likeness of the famous Greek sculpture, Venus de Milo, as both that sculpture and Böttner are without upper limbs. She is exploring the tension between different types of bodies and the ideals of beauty. According to an information plate in the gallery, Böttner commented on the work saying, “I saw that many Greek statues without arms were admired for their beauty. I wanted to show the beauty of the crippled body.” In the drawing, Böttner’s body follows the same form as the sculpture, displayed against an earthy, pink background. The rendition of the body is in grisaille, contorted in an ‘s’ shape with her head looking off the right side. Both the original Venus de Milo sculpture and this drawing have drapery precariously hanging around their hips and their hair is pulled back in a neat bun. The rendering of the face is clearly in the likeness of Böttner. The drawing is about four feet across and four feet tall, which is much larger than other photographs in the gallery, giving the drawing an air of monumentality. The immediate recognition of the Venus de Milo reference captures the viewers’ attention, and, as Preciado said, expands the canon to include those who identify beyond the white, cis-gender, heterosexual body.

Lorenza Böttner, Untitled, 1985, pastel on paper.

Böttner used to pair her works with performances where she would go to venues and the public street, covering her body in a fine layer of plaster and posing as still as an actual statue on a podium until she stepped down and asked, “What would you think if art came to life?”, and would then proceed to dance. For her, dance was a mode of expression by the body that allows social empowerment, and, as Preciado points out, works against the passive nature imposed on the body with functional diversity.

Lorenza Böttner, Untitled n.d., 30.3 x 31.1 cm

Böttner created a great number of works by the time her health declined due to HIV. She passed away in 1994 due to AIDS-related complications at the age of thirty-four but her vibrancy is remembered, with her work expanding the definition of ‘normality’, composing a requiem for outdated norms and limitations set by society. Böttner’s work is a discourse on embracing and accepting different types of bodies and has brought to light the ability to use bodies as a mode of expression, demonstrating how happiness can be achieved through using one’s physical form, even if it is deformed.

Olivia Musselwhite

*Exhibition information: January 25 – March 21, 2020 Art Museum University of Toronto, University of Toronto Art Centre, 15 King’s College Circle Toronto. Museum hours: Tue to Sat 12 – 5 pm.