Shary Boyle borrowed the title of this exhibition, Outside the Palace of Me, from UK poet Kae Tempest’s 2017 song “Europe Is Lost”. With the immersive curatorial plan throughout the exhibition hall, Boyle has assembled her ever-mounting anxieties about global crises in the setting of identity theatre.

In this unique multi-sensory art installation that involves contemporary costume as well as stage design and effects, Boyle analyzes how we see ourselves and our relations with others. In her work, social, political and personal issues, such us economics, colonialism, gender and identity conflicts, and the environmental crisis, go through a metamorphosis. Boyle addresses societal pressures, while also testing the human capacity for empathy. To further modify the experience of the exhibition, visitors can sit down and choose a song from the artist’s playlist as background music. Boyle believes that music changes everything and rhythm and lyrics can make pain bearable and lives more euphoric.

While visitors walk through the long, dark hallway, the first items they encounter are ceramic portraits placed in front of a two-way mirror. The place is seemingly a representation of a dressing room, bringing the interconnection between the object and the observer into focus. Lens (2020), a dark-toned, stoneware bust depicts a woman in front of a mirror. There are holes replacing her eyes, allowing the visitors to look through her empty eye sockets and see themselves inside the reflection. Meanwhile, since this is a two-way mirror, others can observe the entire action from the back side of the mirror. It creates a juxtaposed relationship between object and subject, encouraging visitors to rethink their self-identity, as well as their perception of the outer world.

Lens, 2020, stoneware, two-way mirror. Photo: Vivian Sun

Next there is a colour lithograph, Cephalophoric Saint (2018), showing a Chinese porcelain-headed figure moulding a terracotta bust. The word ‘cephalophore’ comes from Greek, translated as ‘head-carrier’. It is often used in describing beheaded Christian saints who carry their own severed heads. Yet, this work seems to have very little to do with martyrdom. The figure is more likely just creating a mask for an upcoming performance. We can see a narrative in it, a connection with our everyday life, as we have all become performers for an invisible audience. We often change our self-image on social media in order to fit into our ever-changing society, regardless of our true identity. We play, we change and we hide behind our masks.

Cephalophoric Saint, 2018, colour lithograph with opalescent pigment on Somerset Satin paper, 71 × 56 cm. Collaborating printer: Jill Graham. Image courtesy of the artist

Entering a bright room after the dark hallway, we encounter a large, spotlit ‘stage’ and our role changes from observer into active participant. The Painter (2019) is one of the small freestanding porcelain works placed on the edge of the stage. It depicts a faceless woman trying to draw her facial features on the mirror in front of her. She tries so hard to create a face for herself, but the inked fabric in her left hand seems to indicate that she has erased and re-drawn her expression many times. She is in the painful process of creating her self-identity, while being pressured by contemporary social aesthetics that force people to change their appearances again and again for the sake of acceptance.

The Painter (2019), porcelain, underglaze, china paint, lustre, enamel, mirror. Photo: Vivian Sun

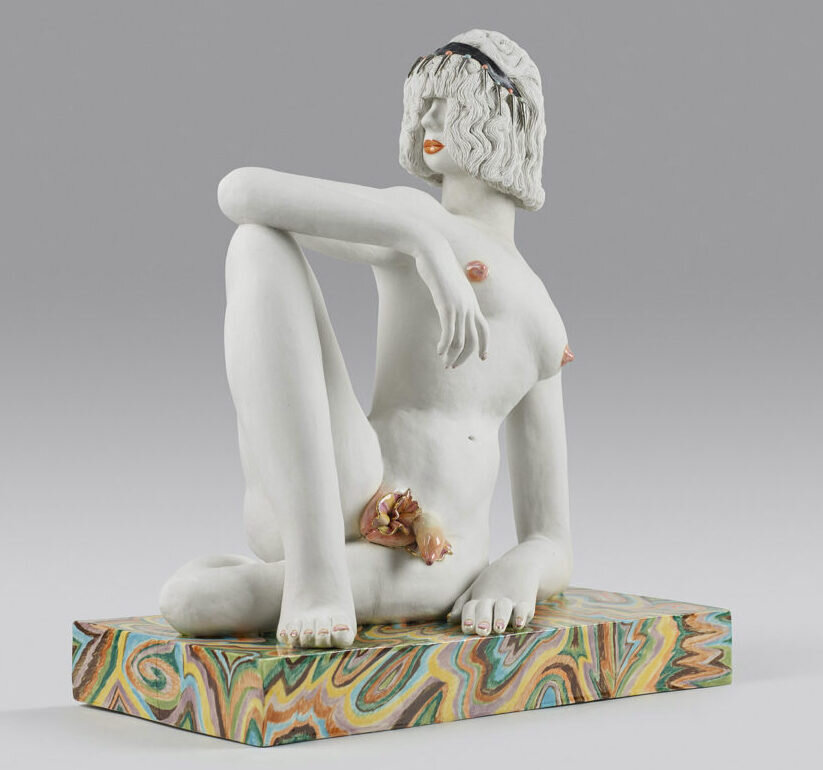

Oasis (2019), another porcelain work, addresses gender and self-identity. Boyle depicts a figure with both male and female genitals, sitting gracefully on the psychedelic base. The figure is snow-white, the colourful glazing only applied to the sexual organs, emphasizing the combined identity of him/her. In art history, artists often used the pomegranate flower in referring to sexual organs. Boyle follows this tradition in the delicate rendering of the genitalia, reminding me of a blossoming flower. The artist may indicate a connection with the social status of the LGBTQ community, as the sculpture gallantly and proudly displays its different body characteristics. As the figure’s face is mostly covered by hair, we can interpret him/her to be anyone, suggesting that the person is still in the process of finding his/her sense of self and acceptance. In this oasis, he/she is away from the critical gaze and judgment of other people.

Oasis, 2019, porcelain, underglaze, china paint, gold and silver lustre, 50 x 42 x 24 cm. Image courtesy of the artist

Moving along to the centre of the stage, visitors meet the star of this ‘performance’, a coin-operated, multi-media artwork named the Centering (2021). Its appearance is flamboyant, as it is decorated with numerous glittering paillettes and multiple layers of voile and fabric. When someone drops a $2-coin into the slot and steps on its pedal, the Centering will start spinning for a few seconds, much like a performer on a stage. These kinds of installations seem to be very popular in pop culture with their glamourous appearance and entertaining movements. Others criticize them as money-eaters because they collect money for their owners. I found the several well-ornamented makeup tools placed at the base of the installation sarcastic, suggesting that appearance is more important than inner beauty. Under this influence people are becoming machines, performing for rewards instead of fulfillment.

Centering, 2021, coin-operated pottery wheel, wood, textiles, beads, crystals, feathers, human hair, sequins, mirror, electronics, foot pedal. Textile collaboration with Grant Heaps. 117 x 66 x 56 cm. Image courtesy of the artist

Then there are pieces grouped around the theme of a puppet show with wax figures placed near the walls. Boyle studied different feminine archetypes in order to recreate them. The most outstanding one is Judy (2021), a woman puppeteer. She has four arms. Each one of her hands is manipulating a different puppet. The circuitry inside the sculpture allows a slight movement of her left hand that activates a small marionette show for the audience. As Boyle wrote in the accompanying introduction, this work is an embodiment of maternal anxiety. It is a critical look at the number of roles a woman is required to play during her lifespan. Judy, in her mutant appearance, with her four arms (definitely an advantage in her occupation), seems to be very focused and totally involved in her show. I am just wondering how many of us have been disfigured, physically or mentally, by our occupations or roles in society.

Judy, 2021, steel, foam, wood, electronics, motor, textiles, wax head, oil paint, human, synthetic, llama and horse hair, silicone hand, stoneware and porcelain puppet heads, 183 x 96 x 66 cm. Animatronic sculpture rotates wrist when motion detector is activated, operating functional marionette. Image courtesy of the artist

The Procession (2022), a large stoneware installation, is a one-of-a-kind parade celebrating our hope for peace. In front of three circular panels with totem animals and scenes from tribal wars a trumpeter is leading this strange parade. Some people are trying to help others get through their difficulties, such us pushing a wheelchair. Hand gestures, symbolizing peace and hope or clasped in prayer are interspersed with people carrying flags of freedom. Yet, there are still fully armed soldiers moving among this street troop. As Boyle points out, “One person’s parade is another’s riot.” At the very end of the possession a man holds up a newborn baby birthed by a mermaid, indicating a close relationship with nature and the hope for a new order in our world. A strong message indeed.

The Procession, 2021, twenty-eight stoneware and bronze figures, installation dimensions variable (group approximately 96cm in length). Wall painting behind sculptures is custom and variable. Image courtesy of the artist

Vivian Sun

*Exhibition information: Shary Boyle, Outside the Palace of Me, February 4 – May 15, 2022, Gardiner Museum, 111 Queen’s Park, Toronto. Museum hours: Mon – Tue & Thu – Friday 10 am – 6 pm, Wed 10 am – 9 pm (free admission 4 – 9 pm), Sat – Sun & Holidays 10 am – 5 pm.