The contrast couldn’t be greater. Three billboards located by an automobile repairshop display photographic compositions by Toronto-based artist Brendan George Ko. The works’ theme can be characterized as the sacredness of nature. They each highlight the beauty of various plant-forms. We have an ode to nature in a starkly industrial setting. These billboards are part of a set of twenty five located across the breadth of the country.

Brendan George Ko, The Wild Carpet, 2021, billboard north of the intersection of King St, W and Strachan Ave, Toronto. Photo: Hugh Alcock

Ko graduated from OCAD some twelve years ago. He has since developed an art practice based on photography and video, which sometimes incorporates poetry, as in this instance. As is explained on the CONTACT website, the billboards are inspired by his assignment for the New York Times that took him to Nelson, BC to meet Suzanne Simard.

Simard is a scientist who has uncovered how trees in natural settings cooperate with one another to aid their survival, a cooperation that is often cross-species even. An article detailing her research was published in 1997 in the prestigious journal Nature. The article employs the term ‘the wood-wide web’, which has since gained popular currency. Essentially Simard explains how trees are not isolated dumb organisms that simply compete with one another. Rather, it turns out that under the forest floor there is a vast network of fungi and roots that enable the rapid exchange of chemicals between trees. In other words, trees communicate with one another, manifesting an intelligence of some sort, albeit of a different order to our own.

Brendan George Ko, Big Lonely Doug I, 2019. Courtesy of the artist

Ko explains that during his formative years he came to appreciate what he calls the spirit of the landscape. And so he was primed to feel the ‘spiritual connections’ of the trees and forest, as he puts it, while on assignment in BC. It is these connections that he aims to communicate to his viewers. His talk of the spiritual betrays an attitude towards nature that sees it as sacred. This is the attitude, many of us recognize, that is shared by the indigenous peoples of the continent. It is a form of animinism, wherein the distinction between animate and so-called inanimate organisms is blurred – everything that is alive merits respect and consideration, one might say.

Ironically science has traditionally encouraged a mechanical anti-animisitic view of nature. Organisms are understood to be at bottom a complex set of biochemical reactions, that is, machines. There is no room for spirit. It amounts to the disenchantment of nature. Consequently, society is licenced to treat trees as lumber and pulp factories. As well, we have no compunction in turning woods and grasslands into monoculture industrial farms, to rip down forests in order to extract tar sands underneath them, and so on. Indeed, Canada cuts down its forests at an alarming rate – one million acres every year – where much of it is used to supply Americans with toilet paper.

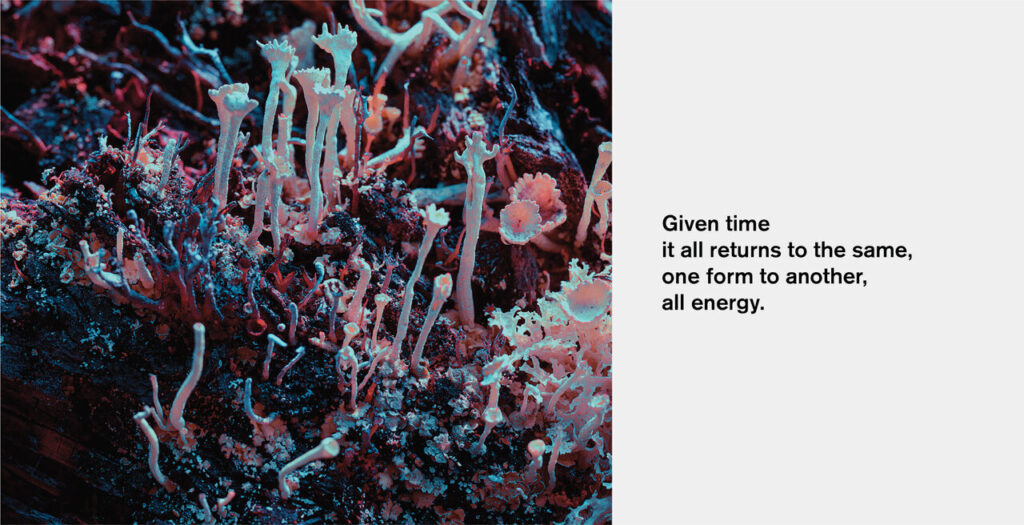

It is ironic in that Simard, a scientist, is helping to reshape this mechanistic view of nature that science has hitherto facilitated. She encourages us to see trees, and plants more generally, as sentient beings. She writes: “By understanding their sentient qualities, our empathy and our love for trees, plants and forests will naturally deepen…” (Finding the Mother Tree, p. 305). Hers, then, is a secular mission to reappraise nature, in contrast to Ko’s quasi-religious appeal to the spirit of nature. Ko’s objective is to enthrall us with the beauty of nature, and thereby ‘reconnect us to it’, as he puts it. He does this by heightening the colours of the photographed imagery and placing it alongside verse. A good example is the image of fungi, titled Pixie Cup, together with the following words: “Given time it all returns to the same, one form to another, all energy.” Nature, he is pointing out, is a wonder to behold. He wants to enchant us by it.

Brendan George Ko, Pyxie Cup Lichen I, 2019, billboard in north of the intersection of King St, W and Strachan Ave, Toronto. Photo: Hugh Alcock

Brendan George Ko, Pyxie Cup Lichen I, 2019. Courtesy of the artist

A problem with his approach, as I see it, is that he borrows the devices of advertising in a venue outside the traditional gallery setting. Not only is the work displayed on advertising billboards, but its format is familiar to most of us. It is a common tactic of advertisers to juxtapose a beautiful image from nature beside some product message, e.g., in order to entice tourists to New Foundland or to sell upscale clothing in a mall. We are so bombarded with images from nature exploited in this way that we have become largely inured to it. That is not Ko’s fault of course. But his aim of highlighting the serenity and beauty of nature, while immersed in the cacophony of our hyperbolic media environment, is extremely challenging. All the same, Ko makes a noble attempt – something that ought to be commended.

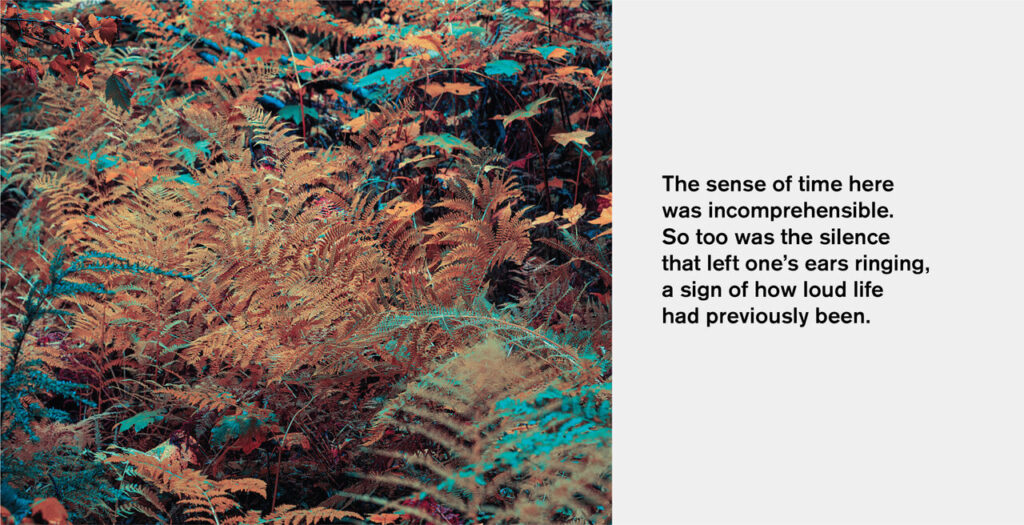

Brendan George Ko, Mixed Ferns of British Columbia, 2020. Courtesy of the artist

As well, the overconsumption Ko is commenting on is central to the production of his very own artwork. In general, his predicament epitomises that of many artists today. How one can comment critically on our unbridled consumer society, when the artworks themselves are in essence products to be consumed by the capitalist machine, for which nature is treated as a resource.

Hugh Alcock

*Exhibition information: Brendan George Ko, The Forest Is Wired for Wisdom, billboards north of the intersection of King St, W and Strachan Ave, Toronto, April 29 – May 30, 2022. Part of Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival 2022.