The title of the show is “Listen!”. That’s listen with and exclamation mark. It’s what you say when you’re asking others to focus. Listen! In this case is not so much about hearing as it is a call to pay attention.

Paying attention is at the core of Hugh Alcock’s work. He produces large intricately detailed drawings of trees and forests. They are full of carefully recorded organic minutia. The forest is the subject of these images but it’s the geometric detail that is Alcock’s true focus. In these drawings, we follow the artist’s observations of the precise bend of each curving line within each forking branch. We watch as he outlines each burl and crevice in the textured bark. With marks of charcoal and chalk, the artist is showing us what he sees.

That these pictures are drawings is significant. Unlike painting, which is primarily concerned with areas of colour, the act of drawing is focused on lines, shapes, and edges. Through the visible markings and scrapes we observe the artist seeing and constructing the image. We see not only the representation of a scene but the representation of observation, the traces of another person perceiving what we now are looking at.

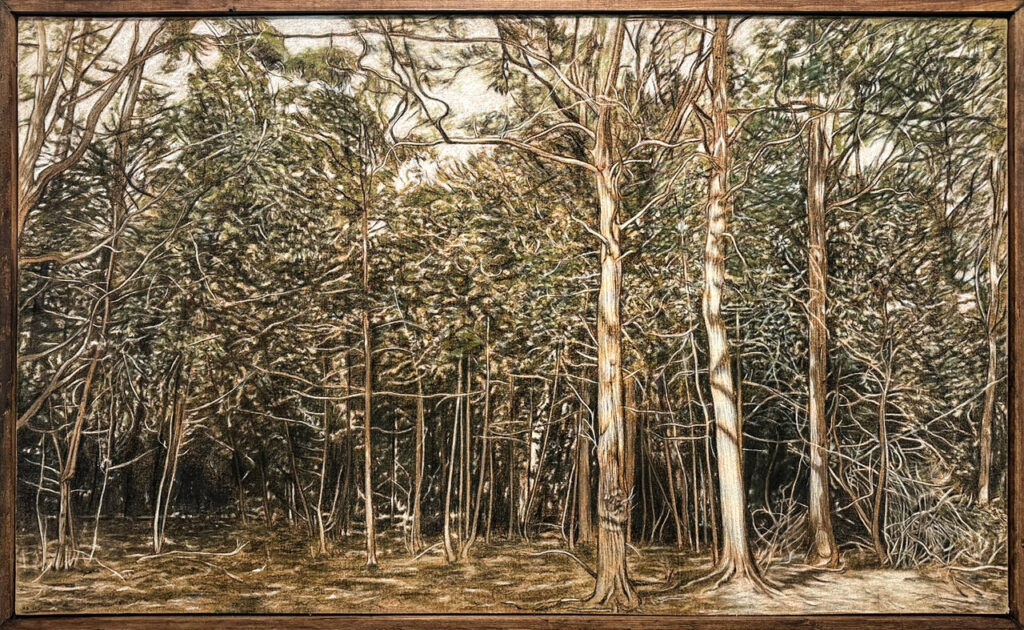

Burnham Beeches, 2021, pastel and charcoal on canvas, 60” x 36”

Alcock’s drawings are based on photographs he’s taken while walking in the woods. The images have been collected over many years and in many different places. Locations include urban forests in Toronto, the Bruce Peninsula, the Beaver Valley as well as photos from Alcock’s native England. He favours dense scenes. His settings place us in locations where we cannot see far into the bush. If the sky is visible at all, it can only be glimpsed here and there. From this large inventory of images, Alcock selects scenes he finds particularly interesting to act as the basis of his drawings.

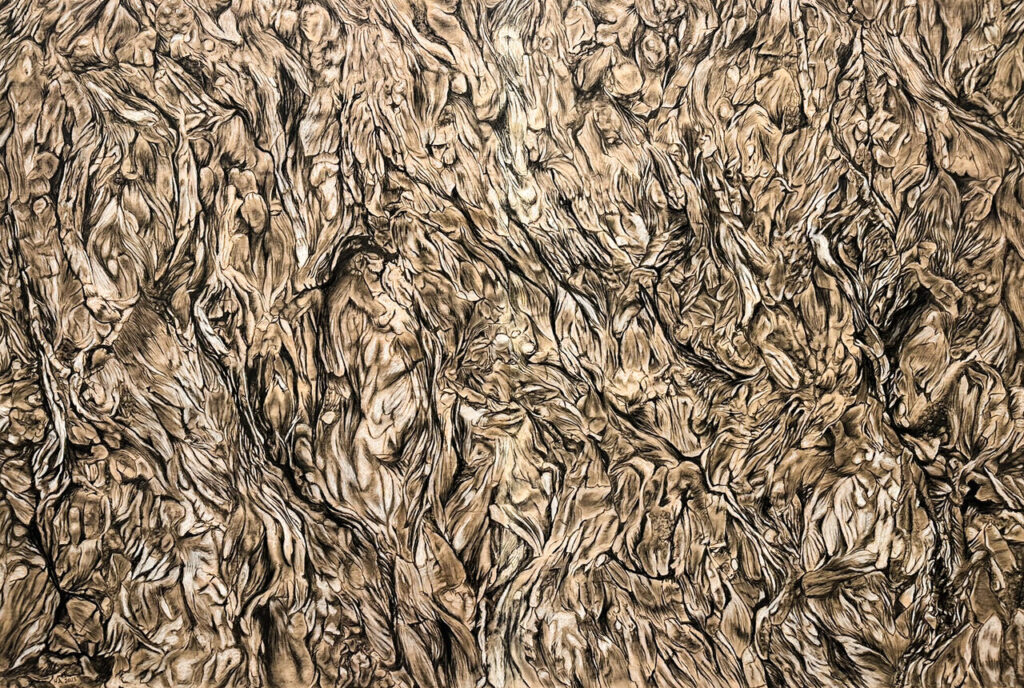

Listening, 2023, charcoal and pastel on wood panel, 48” x 72”

Years ago, when Alcock first began this series of tree drawings, they were done on paper but as the works have grown in scale, he has sought sturdier surfaces. His recent drawings are executed on canvas and wooden panels. The canvas has been primed with a sepia toned medium, while the wooden panels have been left untreated. In both the canvas and the board drawings, the substrate is clearly visible and sets the colour tone across the entire surface. The charcoal and pastel marks comprise a restrained palette of black, white, and subtle greens through which the warm glow of the background is always visible.

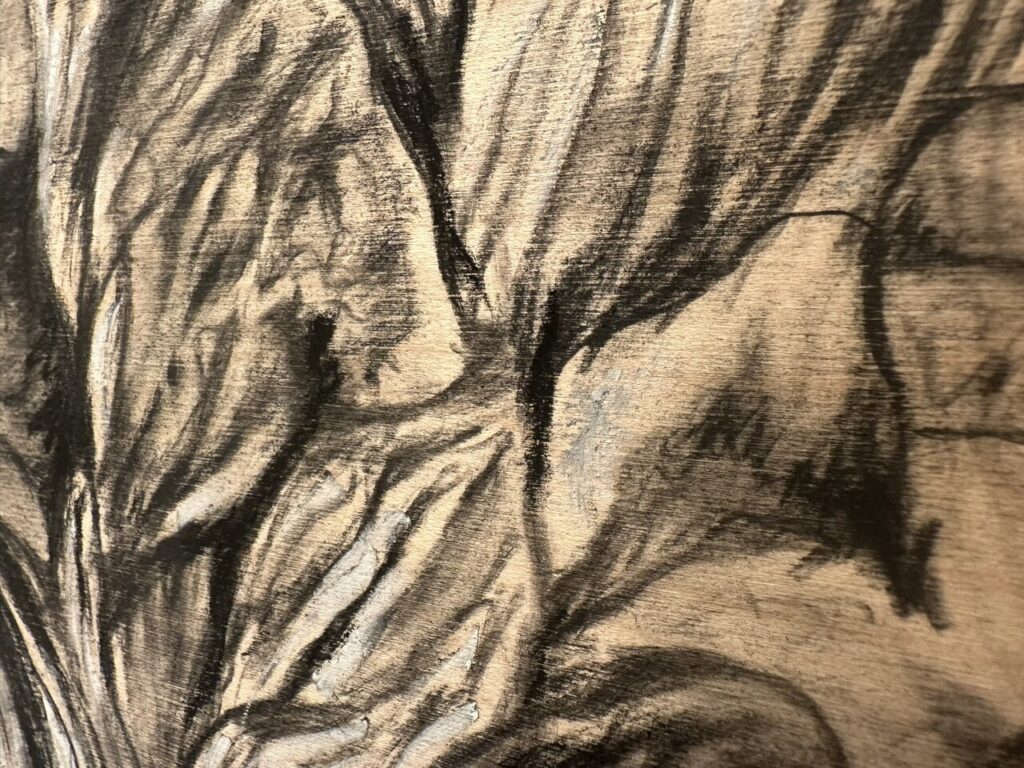

‘Listening’ is a large drawing of tree bark in which the background surface is particularly evident. In this drawing, views of the trunk of a tree from all sides have been combined to create a continuous unwrapped, up-close, field of bark texture. In this piece, the markings of black charcoal and white chalk are a little sparser. From across the room the effect is of roiling organic forms. Up-close the illusion flattens out and we see the scumbled traces of black charcoal and white chalk over the gently swirling pattern of wood grain. The subtle colour shifts in ‘Listening’ are due to variations in the wood veneer. From afar, the image seems to consist of various shades of brown and orange but move in closer and we discover that the only applied materials are black charcoal and white chalk.

Listening, detail

‘Dotard, Burnham Beeches’ is a smaller drawing and with a much thicker covering of pastel chalk. Here there is a density of foliage and an undulating sea of ferns. Dominating the foreground is the tortured hulk of an ancient tree. It bears the full history of growth, accident, injury, and decay as well as the resilience of life. This tree is not from Canada, it exists in a nature preserve in England west of London. It may be hundreds of years old. Oddly, it is unlikely to find a tree of this age near Toronto.

Dotard, Burnham Beeches, 2024, pastel and charcoal on wood panel, 24” x 32”

In his pursuit of subject matter and hunting for old growth forests, Alcock has discovered that there are almost no untouched woodland areas in Southern Ontario. Except in places that are too steep or otherwise inaccessible to logging, none of the forests around here have escaped the axe. In the last two hundred years, every local forested area has been cut down at some point. Even a place seemingly as pristine and protected as Algonquin park is not immune to logging. We are told that logging in the park is done with a light touch: only one percent is harvested each year. But by this measure, no part of the park has trees older than one hundred years. The forests that we typically see are not only artificially young, but also artificially uniform in terms of tree demographics. An untouched forest would be populated by trees of ages several hundred years apart. It’s ironic that old trees have survived better in the shadows of Heathrow’s flight paths than they have in the seemingly pristine landscape of Ontario forests!

Aftermath, Beaver Valley, 2023, pastel and charcoal on canvas, 60” x 52”

Alcock describes his approach as poetic or lyrical. He finds a connection with the naturalism in the poetry of Seamus Heaney and bases the titles of several drawings on Heaney’s work. He would like the work to encourage viewers to “open up their senses to the natural world – sight, hearing, smell and touch.”

Oracle, 2024, charcoal and pastel on wood panel, 56” x 40”

Alcock’s close study of nature is a slow and meditative process. The traces of his activity of observation communicate to the viewer something more than a simple image. It’s not a tree. It’s not an image of a tree. It is the record of someone looking very carefully at a tree. And if we pay attention, and if we follow the artist’s focus, perhaps we’ll start to hear the rustling of leaves, smell the earth and moss, feel a cool damp breeze.

Installation View

Text and photo: Mikael Sandblom

*Exhibition information: Hugh Alcock, Listen!, February 14 – 25, 2024, Gallery 1313, 1313 Queen St. West, Toronto. Gallery hours: Wed – Sat 1 – 5 pm, Sun 1 – 4 pm.